Italy’s Genius Paradox

Why a borderline dysfunctional country produces so many world-changing minds

Why does Italy produce so many geniuses?

The question sounds almost tautological, like asking why Italians speak Italian. That’s just how it is, right? It’s not a coincidence; it’s a condition.

But it’s a paradox that comes to mind every time I marvel at an anonymous fresco in an ancient church -- or waste a morning trying to retrieve a package from the Poste Italiane.

Italy is burdened by a suffocating bureaucracy. It’s inefficient, slow to adapt. The class system is entrenched, institutions are stagnant, wages low. Success often depends on raccomandazioni -- connections -- more than on merit. The Vatican still looms large, with its own agenda.

And yet, the country has somehow been the west’s most prolific crucible of genius, dating back millennia. From the Caesars to Marcus Aurelius. From Masaccio to Michelangelo (by way of Machiavelli). Marconi, Modigliani, Montessori. Fermi, Fellini. Renzo Piano. Riccardo Mutti. Robertos Benigni and Baggio and Saviano.

So, I ask again: Why?

I’ve been informally researching the question for more than a decade. People who know me well -- along with many others I’ve met in coffee bars, sat next to on trains, or (this always gets a smile) met while waiting in various slow-moving lines -- know I like to ask the “genius question.”

“Name a legitimate, world-class, history-changing genius from Germany,” I might say, setting up the premise -- though it could just as easily be France or Spain or The Netherlands or the U.S. “Give me one name and I’ll name three Italians. We’ll keep going until one of us runs out.”

They usually concede the point. That’s when I ask, “Allora, perché?”

The Da Vinci Mode

“Ah, what do you expect?” I get this answer a lot. “We’re Italians! We’re different!”

But a little push is usually enough for conversation to take a philosophical turn. I’ve brought this topic up many dozens of times, and I’ve found that most of the most thoughtful answers fall into three broad areas:

• The Crossroads Effect

Italy’s location is strategic, and over its long history it’s been conquered by the Greeks, the Ostrogoths, the Byzantines, the Franks, the Normans, the Spanish, the French (among many others), each one bringing new ideas, materials, and technologies. Even when Italy wasn’t being conquered its far-reaching commercial ties made it one of the Mediterranean’s most cosmopolitan centers. And at the same time, internal rivalries between city-states created fertile ground for innovation, competition, and patronage.

• The Bel Paese Argument

Italy isn’t just beautiful, it’s aggressively, disarmingly beautiful. Go to Florence’s Piazzale Michelangelo during the “Golden Hour” and gaze across the Arno River and the terracotta rooftops to the Duomo. Or to Naples as a summer storm threatens, dark clouds in a swirl around the shoulders of Mount Vesuvius, its crater lit by a timid sunbeam. The echo in Venice's misty canals. Taormina’s dramatic Teatro Greco. The lovely fan shape of the Piazza del Campo in Siena. It’s not hard to imagine scenes like these not just inspiring great art but convincing the most talented to aim higher.

• The Inheritance Hypothesis

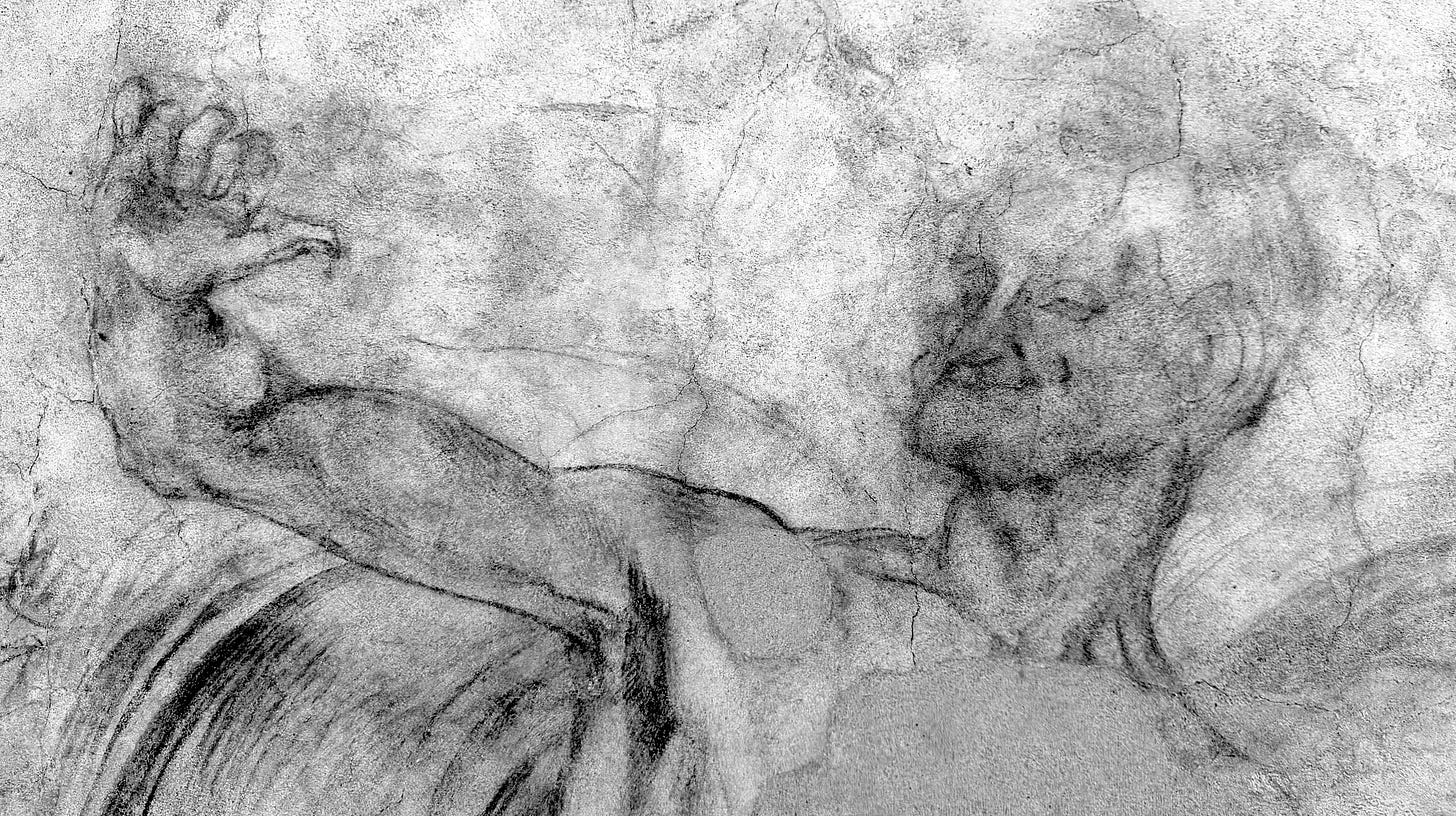

Once Italian scientific, artistic, musical, and political excellence was established it was passed down through generations. Traditions were built as the torch of genius was passed from one hand to the next. For example, 13th- and 14th-Century maestro Giotto inspired Masaccio, who inspired Filippo Lippi, who inspired Botticelli, who inspired Da Vinci, who inspired Raphael, who inspired Caravaggio -- a chain of passed-on inspiration that continues to this day.

But I have a different theory about Italy’s role as a cradle of genius, one I think has at least as big an impact as geography, beauty, and tradition.

Rabbits and hedgehogs

A dark, severe-looking statue of the cloaked Catholic radical Giordano Bruno stands over Rome’s Campo de’ Fiori square, on the spot where he was stripped naked and then burned to death for heresy 425 years ago. Overlooking what is now a touristy market by day and bustling student hangout of bars and restaurants by night, the statue is a grim reminder of Italy’s complicated history.

The square’s name means “Field of Flowers,” a designation that dates to before Bruno met his end there. Campo de’ Fiori remained an actual field of wildflowers into the mid-1400s. It was among the last parts of the city’s historic center to be developed.

Leap forward a few centuries to when Rome became the first western capital hit hard by the coronavirus pandemic. As a journalist, I was allowed to leave home for work-related reasons, and when I did, I found a city with an eerie, post-apocalyptic air. I once stood in the middle of Via Petroselli filming for five or six minutes before a lone car ambled by.

But for Rome’s non-human residents, things could not have been better.

Within a few weeks of lockdown, populations of rabbits multiplied on the Palatine Hill and in Villa Pamphili. Ducks returned to the city’s fountains, and foxes roamed urban parks. Hedgehogs and wild boars ventured onto streets and into neighborhoods.

And flowers returned to Campo de’ Fiori.

They were always there, though underfoot, trampled by market-goers, choked by trash and fumes, ignored by bar-hoppers they remained out of sight. But in an abandoned city, the strongest strains, the ones that survived centuries of abuse and neglect, some of them managed to finally flourish.

That’s how I see genius in Italy. It doesn’t thrive despite the country’s woes; it thrives because of them.

Just as the most resilient flower reaches upward from between the cobblestones, only the rarest minds emerge from the chaos of Italy -- and we all live richer lives because of it.

Post-scriptum:

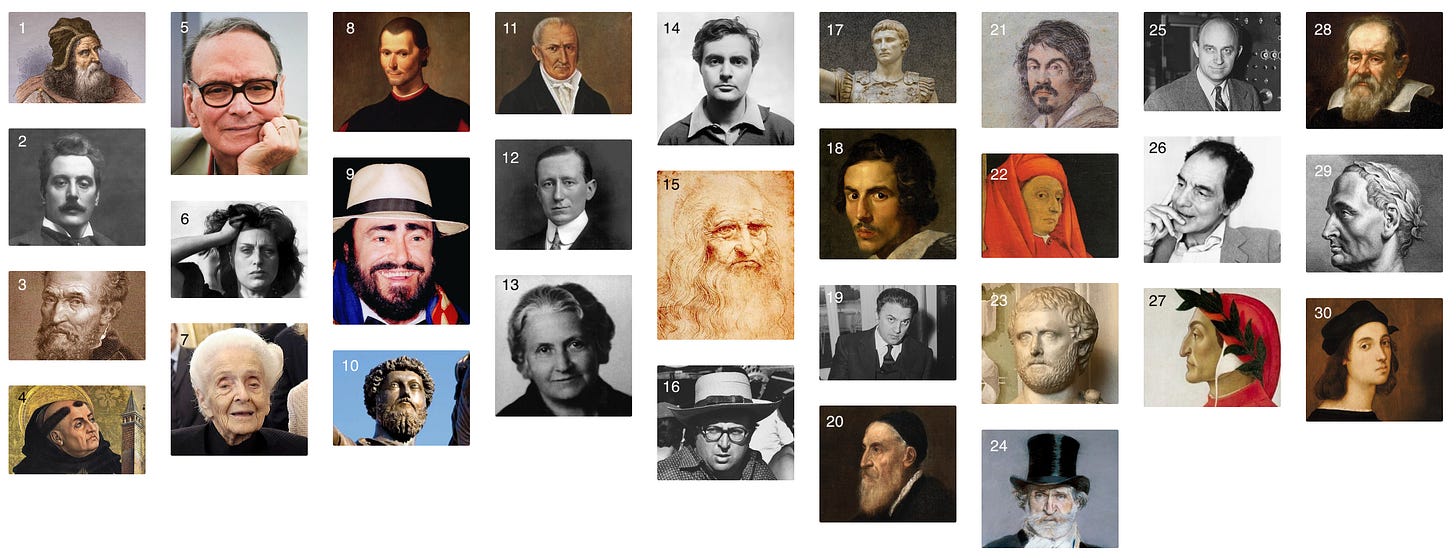

Do you know your Italian geniuses? This week’s post-scriptum is in the form of an informal quiz featuring images of 30 of my favorite Italian geniuses, spread across historical eras and disciplines.

How many can you name? Post your guesses in the comments. (Hint: nearly half are mentioned in this post)

The reader who can recognize the highest number will get a shout-out in the Substack “notes” section. I’ll post the full list here in the comments before next week’s newslettter.

A special shoutout to @Stewmca, who “won” this post's informal genius quiz by correctly recognizing 16 of the 30 faces on the gallery of my favorite Italian geniuses. Honorable mentions to @NeilYoung826626 (who not only recognized many of the names but who also came up with his own alternative list) and @MisterMeridian (my brother who is only on Substack because of me but who I think should start a music newsletter).

See the full gallery at the end of the "Italy's Genius Paradox" post.

Here's the full list of names to go with the gallery:

1. Archimedes

2. Giacomo Puccini

3. Michelangelo Buonarroti

4. Thomas Aquinas

5. Ennio Morricone

6. Anna Magnani

7. Rita Levi-Montalcini

8. Machiavelli

9. Luciano Pavarotti

10. Marcus Aurelius

11. Alessandro Volta

12. Guglielmo Marconi

13. Maria Montessori

14. Amedeo Modigliani

15. Leonardo Da Vinci

16. Sergio Leone

17. Ceasar Augustus

18. Gian Lorenzo Bernini

19. Federico Fellini

20. Titian

21. Caravaggio

22. Giotto

23. Ovid

24. Giuseppe Verdi

25. Enrico Fermi

26. Italo Calvino

27. Dante Aleghieri

28. Galileo Galilei

29. Julius Ceasar

30. Raphael

Great and interesting article! I was really moved hearing about the flowers blooming at the Campo de’Fiori during Covid and how it was used as a metaphor of thriving. As a person of Italian origins it also filled me with an understandable pride and had me pondering the myriad of marvels of these geniuses. Thank you Eric!