The Papacy in a Partisan Age

High stakes for this week's conclave

On Wednesday, the heavy wooden doors of the Sistine Chapel will close behind 133 cardinal-electors and they will begin the process of grappling over the future of the papacy.

Later in the week -- almost certainly no later than the weekend -- Cardinal Dominique Mamberti will step onto the central balcony of St. Peter’s to declare, “habemus papam!”

In between, cardinals will make a decision with relevance far beyond the Vatican’s religious and political scope and in more far-reaching ways than other modern conclaves. I think it could prove to be the most consequential decision the Church has faced in decades.

Why so important? Political polarization.

A ‘Servant of Satan’?

Nearly half the people in the world live in countries that held elections last year: citizens cast ballots in more than 80 countries that are home to at least 3.8 billion people. If there was a single theme to all those elections it was the intense partisanship.

In the United States and across the European Union, in Mexico, the U.K., South Africa, South Korea, in country after country progressives and conservatives dug in their heels and cast stones at the other side.

The list of historically contentious issues is a long one: climate change, refugees, technology, human rights, privacy, security, homosexuality, trade, the rule of law. Arguments are increasingly about insisting the other side is an existential threat rather than policy.

The Vatican has not been immune to the trend. As Pope Francis, who died on April 21, emerged as a leading progressive figure during a 12-year papacy criticism of him swelled.

Historians point out that the Church has always had divisions between reformers and traditionalists. But in recent years that age-old tension evolved into open conflict.

Some examples:

The Vatican excommunicated Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò -- Francis’ first nuncio (ambassador) to U.S. -- for calling the pontiff a “false profit” and a “servant of Satan” for supporting what Viganò called an “inclusive, immigrationist, eco-sustainable, and gay-friendly” Church.

Joseph Strickland, a Texas bishop, was demoted after accusing Francis of “undermining the deposit of faith,” and ultra-conservative Catholic Steve Bannon, one of the architects of Donald Trump’s successful 2016 run for the White House, called Francis a “Marxist subversive,” blasting him for “blaming all the problems of the world” on global populists.

Even U.S. Vice-President J.D. Vance, who converted to Catholicism in 2019 and who met with Pope Francis at the Vatican just 20 hours before the pontiff died, clashed with Francis over an ancient Catholic tenant called “ordo amoris” (Latin for “correctly ordered love”). Vance said the concept gave theological cover to the Trump administration’s controversial crackdowns on migrants and its dramatic cutback to foreign aid; Francis dismissed the notion as a “disgrace.”

Yet there were many others who said Francis relied too heavily on symbolism and did too little to change Church doctrine. “Nobody knows where he goes, he is always changing his mind,” theologian Andreas Lob-Hüdepohl told Politico last year. “There’s no throughline in his doings, no logic.”

A global ‘voice of conscience’

The Vatican will always be the spiritual center for the world’s Catholics, including its ministries, teachings, and charity. But I am focusing here on its influence beyond that realm.

Over the years, when I’ve tried to convince people that the Vatican has real geopolitical influence, I start out with the fact that there are 1.4 billion Catholics in the world and that the Holy See’s views hold sway with them -- particularly in countries where they are the majority.

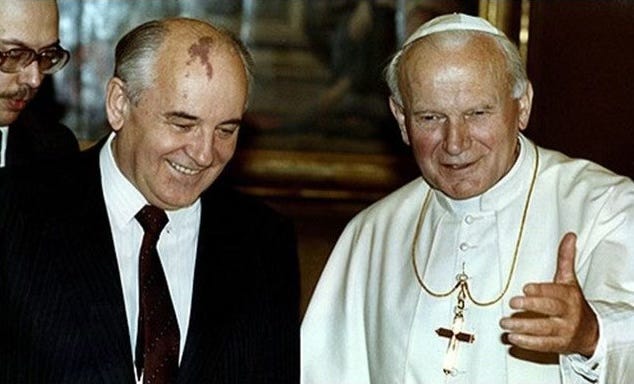

I also note that Polish-born Pope John Paul II played a key role in the fall of the Soviet Union, and that Vatican diplomats served as crucial back-channels in mediating a thaw in U.S.-Cuba relations during the Cold War or in paving the way the settlement of the U.K.-Argentina Falkland Islands conflict, and in other areas.

But I have increasingly begun to see the Vatican’s role in global affairs -- a role relevant to both believers and nonbelievers -- is as a “voice of conscience.”

We’ve seen that in the way Pope Francis succeeded at least partially in casting climate change as a moral issue, of shining a light on the tragic plight of refugees, and in earning swoons from political progressives when in the first months of his papacy he said, “If a person is gay and seeks God and has good will, who am I to judge?”

Don’t call it lobbying

Cardinals entering the conclave take a vow of secrecy, so we may never know for sure what happens behind the Sistine Chapel’s closed doors. But most Vatican observers expect cordiality to carry the day.

I spoke about the topic with John Allen, one of the deans of the Vatican press corps and editor of Crux, a publication specializing in coverage of the Vatican.

“I’ve always said that a papal election is in some ways analogous to the election of a department chair at a university,” he said. “What are the faculty members looking for in a department chair? Fundamentally, they’re looking for someone who is their friend, who they think likes them and will take care of them, someone who will listen to their ideas.

“Honestly, what that person thinks about policy isn’t that important,” Allen concluded.

But something may be happening in the leadup to this conclave that harkens back to the Medieval period when noble families exerted great influence over the papacy.

Today, the word “lobbying” isn’t used in polite company discussing the conclave, but conservative Catholic writer Philip Lawler told The Guardian there were new arrivals in Rome each day representing “all points of view, from across the spectrum … doing their best to ensure that the cardinals understand their concerns.”

Bannon was less measured, vowing a “show of force of traditionalists,” complete with “wall-to-wall” media coverage.

But even more than the possibility of polarization within the conclave, I worry about how a polarized world will interpret the selection of the man who will be introduced when Mamberti steps back from the balcony after his “habemus papam!” announcement.

Will progressives feel betrayed if a conservative pope is elected and starts to roll back Francis’ reforms? Will the schisms that began under Francis deepen if traditionalists are faced with another reformer as pontiff? More importantly, can the Vatican continue to be the essential global “voice of conscience” if its leader is consistently demonized by a large minority within the Church itself?

I’ll give the last word to Allen, who said he thinks cardinals will be measured when it comes to the decision they will be making.

“There is a sense among many cardinals that whoever the next pope is … he will have to address the increasingly acrimonious tone in public debate,” Allen said. “The words that get used a lot are that he must be a ‘healer’ and a ‘unifier,’ and I think those terms reflect the diagnosis that we are living in what is becoming a diseased and disunified world.”

📌 Post-scriptum:

In future posts, this final section will be a separate, provocative sidebar -- usually something at least tangentially related to the main post. But since this is the inaugural edition of The Italian Dispatch, I’ll use this space to introduce the newsletter.

I have been a Rome-based freelance writer and a keen observer of Italian culture for more than two decades. Over that time, my work has appeared in many dozens of publications. But there are still many, fun, intriguing -- and often counterintuitive -- topics I am eager to explore. A lot of them will appear on this site.

The Italian Dispatch will remain a work in progress. That means that suggestions, insights, and even disagreements are not just welcome, but encouraged.

One last thing: please subscribe. There’s no cost involved, and doing so will help shape the newsletter going forward.

He died on Rome's birthday. Is it time for new birth? I agree with the statement, "There’s no throughline in his doings, no logic.” Maybe there wasn't supposed to be, or maybe it was lost since his supporters and foes were always using his words and deeds to affirm their own perspectives rather than allowing themselves to examine PF's line of reasoning while being humbly conscious of their own bias.

Excellent Eric!