A Bridge Too Far?

Italy’s Messina Project May Be Its Most Enduring Obsession

My favorite coastal view in Italy is from Villa San Giovanni in Calabria, looking north -- yes, north -- across the Strait of Messina to Sicily.

On the far side, the city of Messina can look like an afterthought beneath the commanding, often snow-capped shoulders of Mt. Etna, where a faint gray plume sometimes curls up from the crater. In between, a narrow span of steel-blue water is interrupted by an occasional ferry or fishing boat inching across its surface.

From that spot, Sicily feels close enough to touch.

But it’s farther than it looks. The strait is around 3.1 kilometers wide at its narrowest point: nearly two miles, or about 40 New York City blocks. The Vatican City could fit in there four times over.

Yet throughout history, the dream of connecting the two shores has been a temptation as persistent as the smoke drifting from Etna’s crater.

In Naturalis Historia, first-century Roman encyclopedist and natural historian Pliny the Elder described a plan to construct a floating bridge of barges to move captured war elephants to the mainland.

In Medieval times, first Charlemagne and then the Normans commissioned engineers to study the possibility of building a bridge as part of a strategy to wrestle control of Sicily away from its Arab conquerors.

Two centuries ago, King Ferdinando II, of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, vocally flirted with the idea of a bridge.

After unification, future Prime Minister Giuseppe Zanardelli vowed that “sopra i flutti o sotto i flutti” -- over the waves or under the waves -- Sicily would be “united with the continent,” referring to dueling plans to build either a bridge or tunnel to Sicily.

In the 1950s, famed American bridge engineer David Steinman drew up plans for a bridge that were abandoned based on cost estimates. Then, in the 1970s, Italy set up a state-owned company to study the feasibility of the bridge and multiple designs were floated in the 1980s and 1990s.

Then came Silvio Berlusconi, who used the Messina bridge like a campaign prop, announcing it in 2005, then dropping it a year later, reviving it in 2009, and dropping it again four years later.

Between a rock and a hard place

Now, the government of Giorgia Meloni is moving forward with its own plans, which were formally approved by parliament in August -- slipped through during the country’s August slumber, when most Italians are on vacation.

The project carries an initial price tag of €13.5 billion, roughly equal to last year’s government’s budget deficit. Completion is scheduled for 2033.

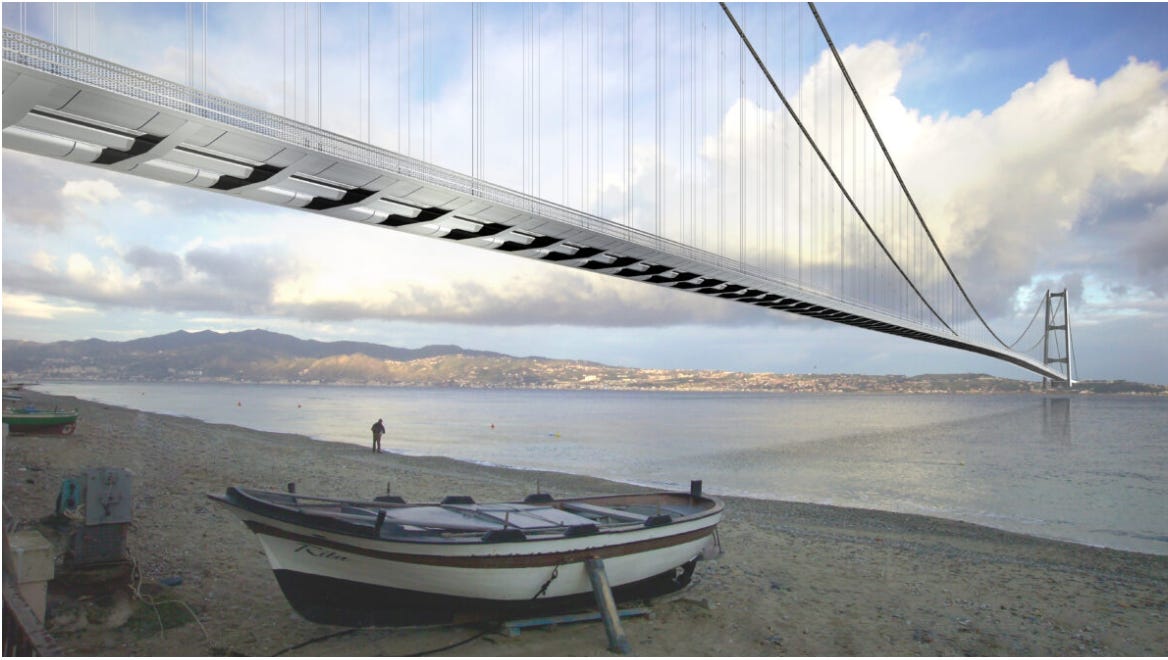

The design calls for two colossal, land-based towers -- each much taller than any structure in Italy, taller even than Paris’ Eiffel Tower -- anchoring what would be the world’s longest suspension bridge. The crossing is planned to feature a six-lane highway and two rail lines.

But there are reasons the daunting Strait of Messina has never been spanned.

In The Odyssey, Homer placed Scylla and Charybdis on these shores. The strait is home to strong, swift currents and strong winds that have left the seabed peppered with shipwrecks dating back to antiquity.

Near the start of the last century, a massive earthquake leveled communities on both sides, reshaping the coastline and leaving more than 80,000 dead. The region still experiences hundreds of small tremors every year and a felt earthquake strikes every few weeks. Seismologists warn it’s only a matter of time before the area’s many active lines unleash another big quake.

Environmental issues are also among the risks: the structure would pose an obstacle to bird migration between Europe and Africa and threaten delicate marine and shoreline ecosystems, particularly on the Sicilian side. Critics fear the project will accelerate coastal erosion and endanger some of the country’s most scenic shores.

Supporters say that by reducing travel time between Sicily and the mainland, it would boost economic development, create thousands of jobs, increase tourism, and lower the cost of goods in Sicily. It would cut emissions from ferries and speed up the deployment of soldiers or disaster relief in an emergency.

The bridge would also be a powerful symbol. It could bolster Italian prestige, proponents argue, and would become a global landmark, like the Golden Gate Bridge in California. A common phrase in pro-bridge news commentary is that it would finally “completare l’Italia” -- complete the country’s unification.

A short history of hubris

The bridge project fits perfectly into an ancient tradition of human overreach.

The Roman Emperor Caligula once had ships lashed together across the Bay of Naples -- longer than the Strait of Messina -- so he could ride his horse across the water to prove a prophecy wrong.

Nero carved out huge swaths of central Rome for his Domus Aurea palace built around a colossal statue of himself as a sun god.

Nearly a millennium later, wealthy Italian families competed in medieval games of one-upmanship, each building towers taller than those of their rivals. The Tuscan town of San Gimignano once had 72 of them, 14 of which survive. Bologna had many dozens more, including the Asinelli Tower, which now leans precariously to one side, and the Garisenda Tower, so notorious that it made its way into Dante’s Inferno.

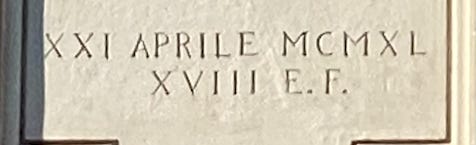

In the 20th century, Benito Mussolini sought to revive the Roman Empire, and he ordered that every date printed in Italy reflect which year of the “Era Fascista” it was, starting with year zero -- 1922, the year of his March on Rome.

But Italy has no monopoly on hubris.

Dubai’s artificial islands are already eroding. Nicolae Ceaușescu’s “House of the Republic” in Bucharest, once the largest building in the world, has never been more than one-third in use. Over the last 25 years, China has constructed dozens of hollow “ghost cities” that will never be fully occupied. And billionaires Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos want to colonize Mars and build space colonies.

Completing Italy

If you want to strike a passionate debate in Italy there are a few go-to topics: food and football, city or regional rivalries, the legacy of Mussolini or Berlusconi, the best way to handle mass tourism, or where to spend vacations. The Ponte sullo Stretto -- the Messina Bridge -- is also on that list.

Is the project another modern example of overreach and hubris? Or something more far-sighted? That depends on who you ask -- and I’ve been asking people for years.

Most people I talk to oppose building the bridge, pointing to its costs, worries about corruption, the questionable utility of it, and likely environmental damage. The country’s infrastructure is crumbling, they say, its population is in decline, and public funds are scarce. Why spend billions on what they say is an unneeded bridge?

But I’ve also met plenty of folks who want it built. They see it as a cultural symbol, a way for the country to show its engineering prowess and its modernity, to prove that it can still do big things. If the goal is to finally “completare l’Italia” more than 160 years after unification, that resonates.

Whichever side people come down on, most would agree the Messina Bridge Project mirrors Italy itself: a long and colorful story about ambition, bureaucracy, skepticism, and symbolism.

📌And another thing

I don’t think the Messina Bridge will ever be built. But if it is, it’s likely that Donald Trump will have had a hand in its fate.

Trump has demanded that Italy and other NATO members increase their defense budgets to at least 5 percent of their gross national product by 2035. That’s an enormous increase from the official 2-percent target that could require lower spending on education, health care, environmental protection, and pensions. It’s also a level that today no NATO country -- not even the U.S. -- spends.

Italy has long been among NATO’s laggards. Last year, it spent around €35 billion on defense, or 1.6 percent of its GDP (it may finally reach the 2 percent this year). But 5 percent seems impossible.

That’s why Guido Crosetto, Meloni’s minister of defense, helped secure a special carve-out. Under the new formula, 3.5 percent of GDP must go to core defense, while the remaining 1.5 percent can be spent on “defense-related investments.”

Days after the carve-out was agreed to, Italy announced that it planned to classify the Messina Bridge project as a defense-related investment. No word yet on whether NATO members will agree to the newest twist on Italy’s centuries-old obsession.

Arriving in Messina on the train ferry after a night on the sleeper from Milan is one of the great moments in European travel. For that reason alone, I'm in the ‘no bridge’ camp…

Coming from this part of the world—growing up with Etna always in sight and learning to swim in those waters while gazing at the opposite shore—your article felt like listening to an old friend recounting family stories.

Just last week, my father said: “I hope we’ll see that bridge one day. Maybe I won’t be here anymore, but people from all over the world will come to see us—not through the lens of being one of the poorest regions of Italy, but as a symbol of strength and future.”

I still have my doubts about that project. But I would like to believe in my father’s dream.