Who is Italy for?

As tourist numbers soar and residents vanish, the soul of the country is at stake

“Oh, che peccato,” someone will say -- “What a shame.” Then comes the head shaking over the latest once-reliable trattoria to have become a caricature of itself.

In Italy’s most visited cities -- Rome, Florence, Venice, Milan, Naples -- a good location can be a gilded curse. As costs rise and locals move out, the temptation to abandon the remaining residents and cater to less discerning tourists becomes almost irresistible. One by one, the classic family-run eateries disappear.

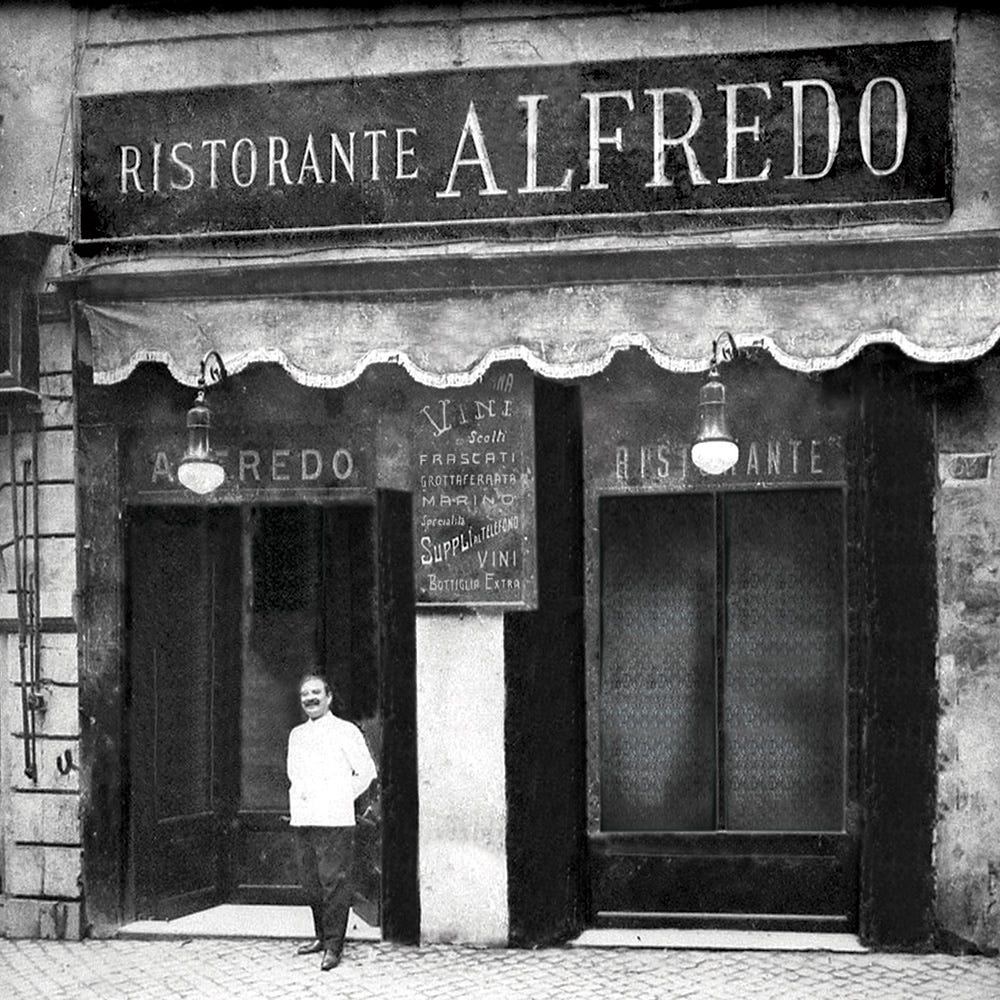

I first saw the trend unfold at Rome’s famous Ristorante Alfredo alla Scrofa, the birthplace of Fettuccine Alfredo1.

When I worked in U.S. restaurant kitchens, various Americanized versions of the dish -- Chicken Alfredo, Shrimp Alfredo, Four-Cheese Alfredo, Cajun Alfredo, Lemon Alfredo -- were staples. For some, they even passed for haute cuisine. I could prepare them with my eyes closed.

Ristorante Alfredo alla Scrofa was once a landmark of Dolce Vita Rome. Its walls still flaunt photos of Marlon Brando, Audrey Hepburn, Frank Sinatra, Gregory Peck, Sophia Loren, Dean Martin, Federico Fellini, Ella Fitzgerald, Brigitte Bardot, Charlton Heston -- even Gabriele D’Annunzio -- most of them posing with a plate of the restaurant’s signature dish. But today, it’s the knd of place locals warn you about: over-priced, theatrical, a fossil preserved in tourist amber.

I ignored the warnings and ate there once. The waiter’s canned patter included telling me I looked like Sinatra as he stirred the fettuccine, butter, and cheese tableside. My secondo took so long to arrive that I was no longer hungry. Then came the sticker shock of the bill. I still cringe at the memory of that night.

Since then, the list of once-inviting places I avoid, not just in Rome, but in every major city, grows every time the subject comes up among long-time residents, whether Italian or foreign.

A Colosseum-shaped ashtray

The worst damage from mass tourism isn’t always visible.

Fragile ecosystems like Venice’s lagoon or the trails in Cinque Terre are damaged. Monuments, museums, and historic sites wear down under the weight of simple foot traffic. Roads, public transport, electric grids, the water supply, phone networks, waste systems all feel a strain.

And as the pressure builds, so does anti-tourist resentment.

Some examples are outrageous. Remember Ivan Danailov, the guy who carved “Ivan + Hayly” onto the walls of the Colosseum with a key? “I didn’t know it was ancient,” he explained when caught. Or the Saudi man who drove a Maserati down the Spanish Steps in Rome? The topless woman who went swimming in Florence's Piazza Santo Spirito?

And that’s without getting into the embarrassing details of Jeff Bezos and Lauren Sanchez’s recent wedding spectacle in Venice.

I could go on. But the point is the same: there is no shortage of tales of tourists behaving badly.

But beneath the headlines there is something far more corrosive.

Entire communities are being hollowed out. As residents flee rising prices and a declining quality of life, neighborhoods turn into stage sets. Local economies become one-dimensional. Culture and traditions turn into commodities. The values and lifestyle that drew so many visitors in the first place begin to disappear.

Restaurants are often the first to go. With a few brave exceptions, the classic neighborhood osterie and trattorie vanish in rings emitted from a city’s most touristed areas, like the spread of a virus. Ristorante Alfredo alla Scrofa, deep in Rome’s historic heart, is practically at ground zero. It never stood a chance.

“I didn’t have many options when I wanted a hardware store, a butcher shop, a dry cleaner, or even a restaurant without an English-language menu,” one long-time friend who lived for a decade near the Spanish Steps likes to say. “But if I ever needed an extra Roman Holiday refrigerator magnet or a souvenir ashtray shaped like the Colosseum, I was in good shape.”

Italy, overbooked

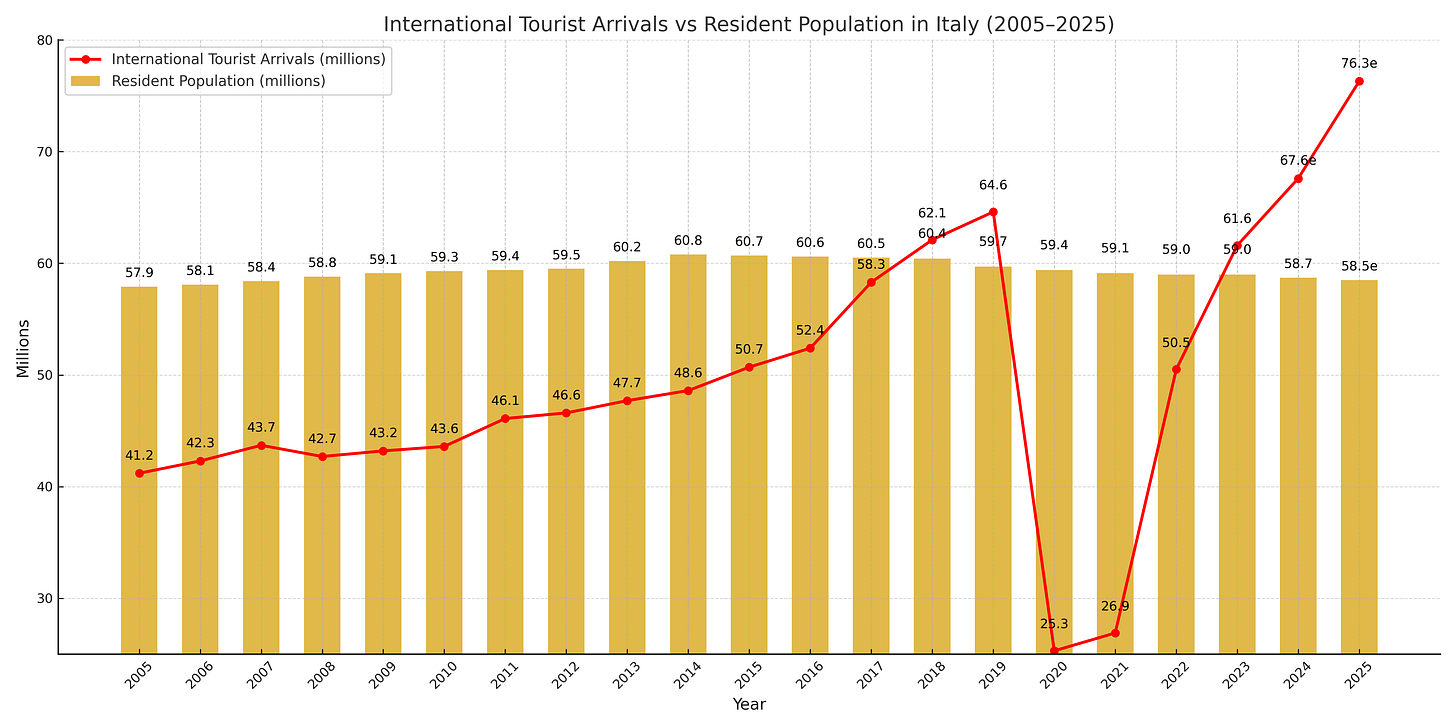

In 2018, for the first time ever, Italy had more international tourist arrivals than residents: 62 million visitors in a country of 60 million.

Then came the coronavirus pandemic. Airports emptied. Streets fell silent. In a strange way, historic centers briefly became livable again.

But then tourism roared back: 2023 nearly matched 2019’s record; 2024 easily surpassed it; and this year is almost certain to blow past both even as Italy’s resident population continues to shrink. Barring another world-halting event, the imbalance will only grow wider.

Yet, despite those gaudy numbers, Italy isn’t even in the global tourism top three. It’s in a tight race with Turkey for fourth place behind perennial giants France, Spain, and the U.S.

France sits comfortably in the top spot. The French will welcome an estimated 94 million arrivals this year in a country with a population of 67 million -- only a little larger than Italy’s. But France seems able to absorb the impact. How?

Infrastructure is important -- more hotel rooms, a faster and more comprehensive rail network, more airports. But just as important: it spreads out the load.

In Italy, more than half of what will soon be 80 million annual tourist arrivals are funneled into just five parts of the country: Rome, Florence, Venice, Milan, and Naples (numbers for Naples include the Amalfi Coast, Ischia, and Capri). Visitors often follow a narrow and overwhelmed circuit, leaving entire regions under-visited.

To wit: last year, seven of Italy’s 20 regions attracted fewer visitors than Rome’s Colosseum alone. Five regions had fewer visitors than the Uffizi Museums in Florence or the ruins of Pompeii. Four were outdrawn by the Leaning Tower of Pisa.

There are signs of hope. The Uffizi Diffusi initiative (the name means “Widespread Uffizi”) launched four years ago is a good example. It relocates artwork that once languished in storage or obscurity in the main museum to lesser-known Tuscan towns, relieving pressure on Florence and reviving cultural interests further afield.

But convincing enough tourists to venture to the wild peaks of the Majella National Park in Abruzzo, to discover Sardinia’s ancient Nuraghe fortress, the Byzantine mosaics of Ravenna, the sprawling grottoes of Le Marche, Sicily’s Baroque beach town of Scicli, or to any of the hundreds of hilltop towns like Civita di Bagnoregio would be an enormous challenge. It would require massive investments in marketing, infrastructure, and transport.

Don’t hold your breath.

📌 And another thing:

In one of the earliest posts for The Italian Dispatch, I wrote about the unlikely shared devotion to St. Augustine between the newly-elected Pope Leo XIV and U.S. Vice-President J.D. Vance.

In researching the piece, I revisited the Basilica of St. Augustine, just behind Piazza Navona. Despite its proximity to what might be Rome’s most visited square, it was nearly empty.

It's a lesson I try to remember. In Italy, salvation may lie just beyond the line of sight.

Stray from the selfie sticks and gelato seekers -- sometimes a few minutes is enough -- and Italy can reveal itself as more than a theme park. A tourist can become a traveler, a wanderer, someone who can stumble upon a forgotten chapel, marvel at an overlooked Madonnella, or dine at a trattoria that somehow resisted the expanding rings of touristification. That’s an Italy worth getting to know.

Come back next week for another dispatch.

The history of Fettuccine Alfredo in Italy is a bit of a soap opera. The dish was invented by Alfredo Di Lelio, who opened a restaurant in the building housing Ristorante Alfredo alla Scrofa, before World War I. But he sold that spot in the 1940s, and a few years later, he opened Il Vero Alfredo nearby, which is still run by Di Lelio’s family. Both claim to be the original. I ate at Alfredo alla Scrofa and, afterwards, didn’t have much desire to try out its rival.

Unfortunately, I agree with this analysis. Take Bologna, for example. We have a large number of foreign residents here, primarily due to the University of Bologna and the presence of many American universities. Since foreign tourists discovered it, word of mouth has started to spread. The city's high quality of life, services, safety, strategic geographical location, history, and food options are among its greatest assets. Many Europeans and non-Europeans are interested in purchasing a home here. They are looking for large houses in historic buildings, which has pushed property prices to skyrocket. Meanwhile, the city is experiencing a slow but inexorable erosion of its soul. I would add an aspect that does not concern cities, but small towns and rural areas where many foreigners have been living for years, and which have become nursing homes for wealthy foreigners. This also makes it clear that Italy's future is increasingly out of the hands of Italians. Di doman non v'è certezza....

Hey! I use a Colosseum ashtray! (not really.....!!)

That chart is depressing. Was it from ISTAT?

As someone who feels like a visitor here in the country she was born in (I mostly grew up in the US but was born in Italy) I can say that the state of mind is more important than birthplace. I have an Italian passport and last name & I speak Italian w/o an accent, but I still feel like foreigner sometimes. I know some foreigners who have lived here for a long time and who fit in better than I do most of the time.