A Wrinkle in Stone

Rome once valued age and experience. Now it’s valued for them

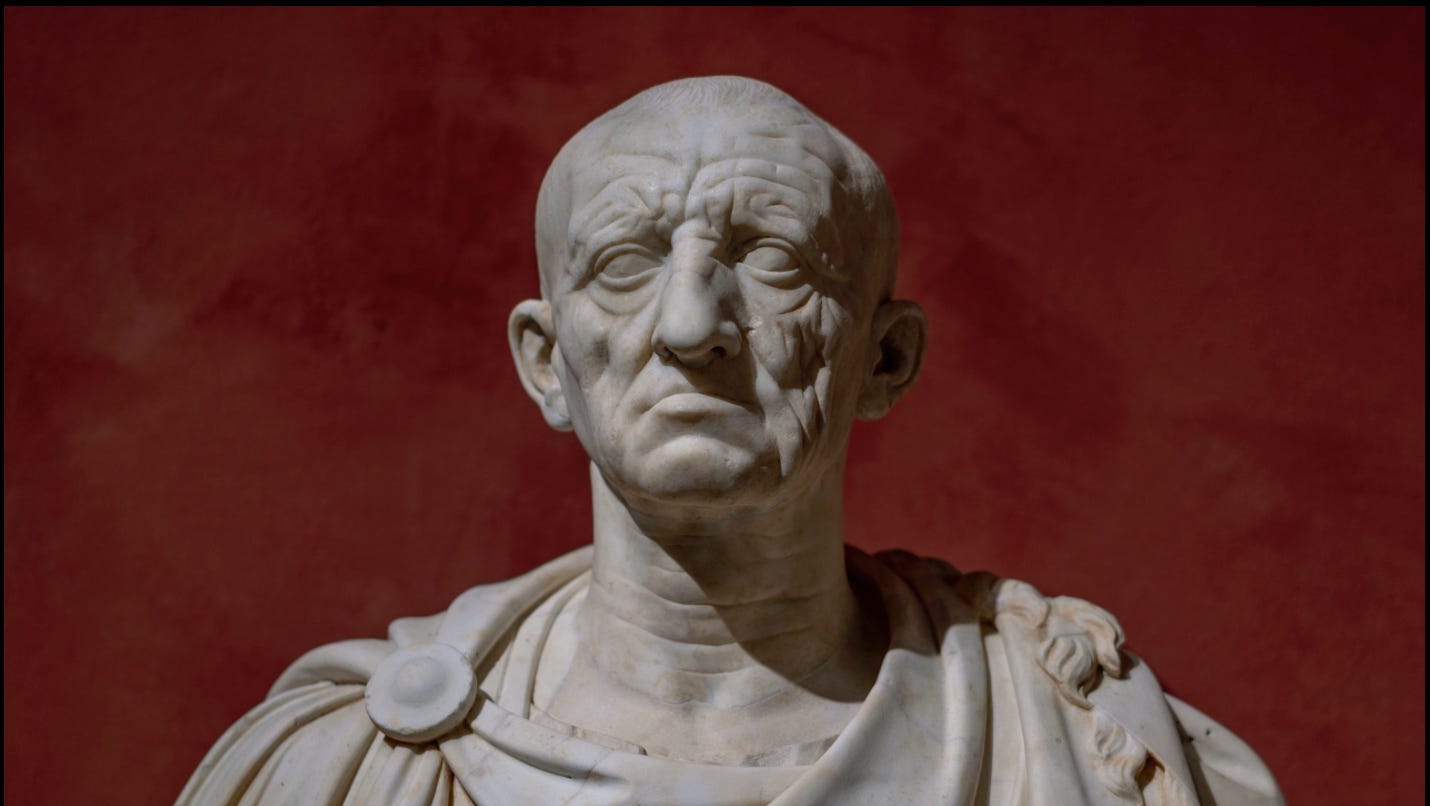

The thing that strikes me most about many early Roman statues has nothing to do with their artistry or balance. It isn’t the grandeur. It’s not the symbols of power they display or the way subjects are posed.

It’s how damn unflattering they are.

These were rich and powerful men -- the highest echelon of Roman society -- and yet they are memorialized with sagging skin, hook noses, uneven features, tired expressions, and wrinkles forced on them by age, worry, and conflict.

Some statues from the Roman Republic are so intensely veristic that modern-day doctors can knowledgeably speculate about the underlying health conditions of many of their subjects, recognizing scoliosis, goiters, and even neurological disorders.

Public life in the middle and late Republic must have seemed long and brutal. Influence wasn’t inherited neatly, and leaders were not yet claiming it by divine right. Power accumulated slowly, through service, survival, compromise, reputation. It was built with great effort over decades. And it showed.

Faces of the dead

I think cultures reveal what they fear most by what they try to hide.

In ancient Greece, discomfort came from chaos and the unpredictable nature of life. Greek sculptors responded to it with idealized order: perfect proportions and bodies frozen in eternal youth. They were less portraits than arguments. They showed what they thought a human should be.

Rome, at least during the Republic, made a different choice. Instead of asking art to imagine a better man; it asked it to record a real one. A fleshy neck implied endurance. A lined forehead, judgment. Even scars carried meaning: they showed a body had been used and tested, and that it survived.

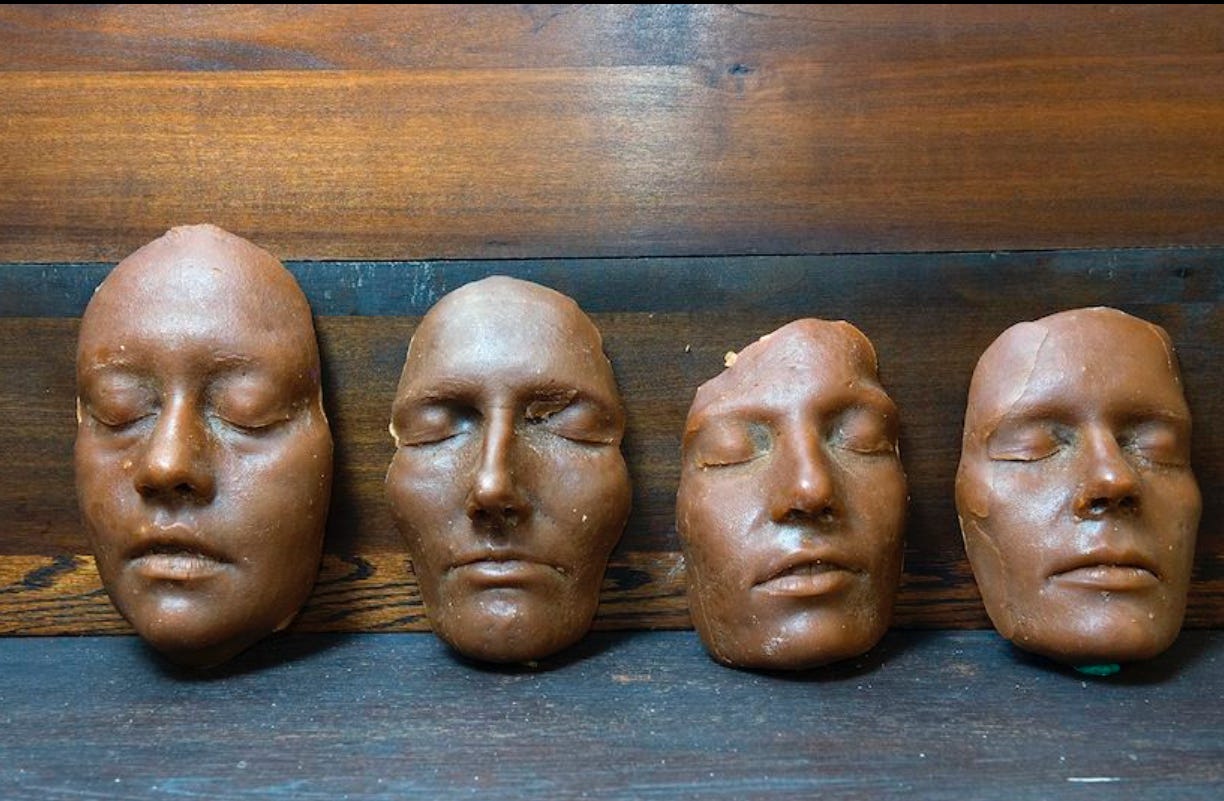

The same sensibilities shaped how Romans related to their past. In Republican Rome, the homes of aristocrats contained wooden cabinets filled with rows of wax ancestor masks -- imagines -- made just after death and displayed prominently near the entrance. Children studied them and memorized details from the lives they represented. The masks were taken out and worn for funeral processions.

Every time a family member entered the house they were confronted by the faces of their ancestors, each of them as they looked at the end of their lives: old, spent, mortal.

In Republican Rome, a citizen’s wrinkles weren’t flaws. They were credentials.

Forever young

After Caesar Augustus ended the Republic, portraiture changed. He reigned for more than four decades, but judging from his statues he barely aged. Augustus is always portrayed as youthful, athletic, at ease -- more like a Greek god than a Roman magistrate.

It wasn’t vanity. Augustus redefined power. Under the Empire, authority didn’t have to be earned; it had to seem permanent. Continuity was more important than truth.

It remained that way for centuries. Imperial portraiture became so idealized and symbolic that experts today often struggle to differentiate between historical figures. By the time the Empire collapsed, sculptors had long since stopped carving faces that looked like their subjects.

Rome, unretouched

For a modern-day visitor to Rome, all of this may feel distant, like something behind museum glass.

At first glance, the Eternal City doesn’t seem so different from any other tourist hotspot. Search for #Rome on social media and you get the same glamorous poses, filtered sunsets, and food photos found everywhere.

But I like to think the city is an unwilling participant.

Rome is a gritty, flawed, and confusing metropolis that shows its age. The city has been sacked and rebuilt, burned and abandoned, venerated and stripped for parts. It has survived floods, plagues, dictatorship, and, now, over-tourism and civic indifference. Its buildings are scrawled with graffiti, its streets cratered with potholes, and its trash bins overflowing. Most of the city’s leadership lands somewhere on a scale that spans from corrupt to ineffectual.

Yet it endures. Not despite these defects and not even because of them, but because they remain in plain view. Rome wears its history the way the Republican statues in its museums wear their wrinkles -- not as decoration, but as evidence.

📌 And another thing

There’s another layer to this that didn’t fully take shape for me until I read a memorable Substack essay, I Who Have Never Stuck a Needle in My Face, by Erin Nystrom.

The piece traces a pattern across seemingly unrelated status markers: from powdered wigs to manicured lawns to plastic surgery. It argues that cultural values don’t shift only as the culture’s fears evolve, but as the power to obscure those fears becomes more accessible. What begins as elite signaling loses its force once it can be copied by non-elites. That’s when it’s abandoned.

Reading it helped me see Roman verismo in a new light. Wrinkles and other signs of experience could function as credentials only as long as experience itself remained scarce and meaningful. When power stopped depending on participation as much as projection, honesty became a liability. The face -- just like wigs or lawns -- stopped recording reality and started managing perception.

In ancient Rome, the shift happened after Augustus. And it’s not hard to conclude we’re living through a version of it now, right before our tired eyes.

Nystrom writes that being “naturally” beautiful could become the next signifier of wealth, implying a person’s access to the resources and lifestyle required to age gracefully. The topic is a little outside my lane, so I won’t speculate.

But what sticks with me -- and what Roman statues communicate clearly -- is the larger question: what happens to power and influence when authenticity and truth become luxuries? I have my theories. History has taken us through that turn more than once.

Wow, Mr. Lyman. I think your best article yet. Touches on so many universal themes and weaves together yesterday, today and tomorrow so seamlessly… bravissimo!!!

Love the analogy and a very enlightening piece.

It's something that I particularly like about Rome. It is a mix of old and new and everything in between. Many places are attempting to obliterate the past. as if getting rid of old buildings and names is going to eliminate any of the history, particularly the bad stuff. I know it's a sensitive topic and understand that in many instances it has to be done for the society to deal with it and move forward.