Almost Roman

For outsiders, living in the Eternal City is an apprenticeship that never ends

Annamo bene, eh! Stamo a Roma1

I was speeding toward Castel Sant’Angelo on my motorino late one evening. Traffic was light -- just one other scooter on the road -- as I zipped toward a pedestrian crosswalk, where a woman and a teenage boy were crossing.

I drifted to the left side of the three-lane street to cross well in front of the pair, while the other rider edged to the right. Suddenly, in panic, the boy broke away from the woman and started running back to the side where they’d started. Then, seeing how far it was, he changed his mind again and bolted past the startled woman toward the left side. She froze in the middle of the crosswalk, unsure what to do.

I saw the boy’s change of direction and veered sharply to the right to pass behind him. But the other rider was already cutting left. We were on a collision course!

I pumped the rear brake and slowed slightly, just as the other rider accelerated. He shot by a meter or two in front of me and we cleared the crosswalk without incident. In my mirror, I saw the woman throw her arms around the unfortunate boy, who was sitting on the curb.

A few seconds later, I put my feet down at a stoplight, my veins still pumping with adrenaline. The other motorino was already there. I turned and shouted, “Quelli volevano morire!” -- “Those people wanted to die!”

The other driver did a double take after hearing my accent. “Aspetta!” he said. “Wait -- you’re not Italian?”

I nodded, still breathing hard.

“You may be a foreigner,” he said, shaking his head. “But you drive like a Roman.”

My chest swelled with pride.

Roma nun se fa riconosce2

That evening came to mind after The Italian Dispatch published a Q&A with historian and writer Anthony Majanlahti.

Majanlahti, a Canadian, is best known for his book The Families Who Made Rome. But his most ambitious project is still in the works: The Eternal City, a comprehensive urban history of Rome that will recount the story of the city from its earliest roots to the present day.

I asked Majanlahti how he’d respond to a critic who argued that such an important work should be written by a Roman.

“I’d tell them that I am a Roman,” he said. “I came [to Rome] from abroad and chose to live my life here. That’s what being a Roman means. It has very little to do with where you were born. Cicero and Hadrian weren’t born in Rome.”

Majanlahti is correct. But judging from that essay’s comment section and later conversations, few native-born Romans would agree.

Che stai a dì’?3

Ask one Roman what makes someone Roman and you’ll get an opinion; ask two and you’ll start a debate; ask three … and they’ll find a table and one of them will order coffees.

The answer you hear most often is that to be a Romano di Roma -- a Roman of Rome -- a person’s family must have been in the city for at least seven generations, one for each of the city’s seven hills. It takes at least that long, Romans say, for the city’s contradictions, traditions, and charms to become ingrained.

I’ve also heard other, more generous standards.

Some talk about geography: someone should be born within the Aurelian Walls, or at least within the Grande Raccordo Anulare (Rome’s ring road).

Others say it’s a temperament: a Roman should remain calm amid the city’s chaos, treat written rules as suggestions, and understand the unwritten rules like a liturgy.

Some friends talk about the role of loyalty, whether to their quartiere (neighborhood), to their football team (only AS Roma or Lazio), or to the same baker, butcher, or bar they’ve gone to since childhood.

But the thing that ties all those conversations together is that they’re usually explained in Romanesco -- the city’s own dialect -- where words like annamo, avoja, or ahò4 can each take on the meaning of an entire sentence. The dialect is performative, part swagger, part opera, part shrug. I think a person can study Italian for years, but they’ll probably never sound Roman unless they were scolded in Romanesco as a child.

Boh?5

The thing is, except for some of the unwritten rules I enjoy examining and maybe the temperament, I don’t meet any of these qualifications. Yet, I feel more at home in Rome than I do anywhere else.

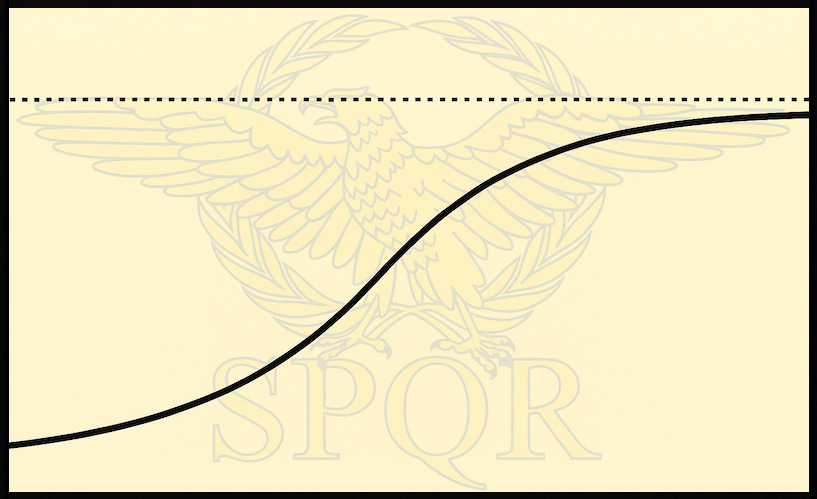

I think that for outsiders, understanding Rome follows an asymptotic curve -- a geometric figure bending toward a line, its asymptote, without ever intersecting.

I’m surely further along that curve than most foreigners. I’m probably further along it than many non-Roman Italians living in the city. In many ways I think and live like a local. But really being one? No, not possible. Despite my street-tuned motorino driving style, that’ll always be out of reach.

📌 E n’antra cosa.…6

This essay was originally going to be about the extent to which someone born abroad can become Italian.

It made sense at first. In the same way, the points made about belonging in a city like Rome can apply to any group whose membership is rooted in birth: Italians or French or Germans, of course, but also most religions, royal families -- even the Mafia.

But being Roman is different from any of those because there’s no formal arbiter or standard to decide who can be a member of the group and who cannot.

Rome has always been porous. The city has been absorbing outsiders for millennia: Sabines, Etruscans, Greeks, Jews, North Africans, Germanic tribes, Spaniards, Sicilians, Albanians, Romanians, and now Filipinos and Bangladeshis. Each wave leaves its mark on the city, and, in a way -- and after generations -- becomes Roman too.

Come back next week for another Dispatch.

(A note for regular readers: I first previewed this piece Nov. 10 while testing the layout, but the final version went live Nov. 11.)

The section headings this week are all in the Romanesco dialect. This one means: “We’re off to a good start, no? We’re in Rome.” (Usually said ironically)

Literally, “Rome doesn’t let itself be recognized.” But it’s probably closer to “Rome doesn’t make itself easy to understand.”

“What are you talking about?” or “Are you serious?”

Annamo (or ’namo) means “let’s go”; avoja means “you got it” or “yeah, right”; and ahò means “Hey!” / “Come on!” / “Are you kidding me?”

The meaning depends on tone: “Who knows?” / “Whatever.” / “What can you do?” / “I don’t know what to say.”

“And another thing….” (the normal name for the P.S. section of The Roman Dispatch)

I love your coat of arms!!!

I really appreciated this. As a foreigner who lived in Rome for five years, it really resonated with me. I only drove occasonally, so I never developed have your road skills. I was pretty good at Romanesco though, thanks to the folks I worked with. One of whom was actually a Romano de Roma!