Italy’s Fiery Soul

Grappa has warmed soldiers, laborers, and Hemingway. Should it be on your dinner table?

Like most people, I swore off grappa the moment the first fiery sip scorched its way down my throat. I coughed and blinked through watery eyes, convinced the heavy, attention-grabbing bottle of what tasted like high-octane moonshine wasn’t for me.

Yet today, years later, I have become a grappa evangelist. I bring bottles as housewarming gifts. I shun restaurants that don’t stock the good stuff. I cajole dinner companions to try a sip or two of the maligned, misunderstood spirit for themselves. If you catch me outside Italy, chances are I’ll have a silver flask of grappa tucked into my backpack.

I’ll be the first to admit it’s not for everyone, and I don’t mind. After all, how many things can you name that everyone likes and that are still worthwhile?1

But why don’t more people enjoy it the way I do? The answer is simple: while it’s true that good grappa can be very, very good, it’s also true that bad grappa can be very, very bad. And most grappa is bad grappa.

Italian bureaucracy deserves a lot of the blame.

‘Poor Man’s Brandy’

Wine has been part of life on the Italian peninsula for at least 4,000 years. Distilled spirits, in comparison, are newcomers, arriving in the Middle Ages from the Arab world.

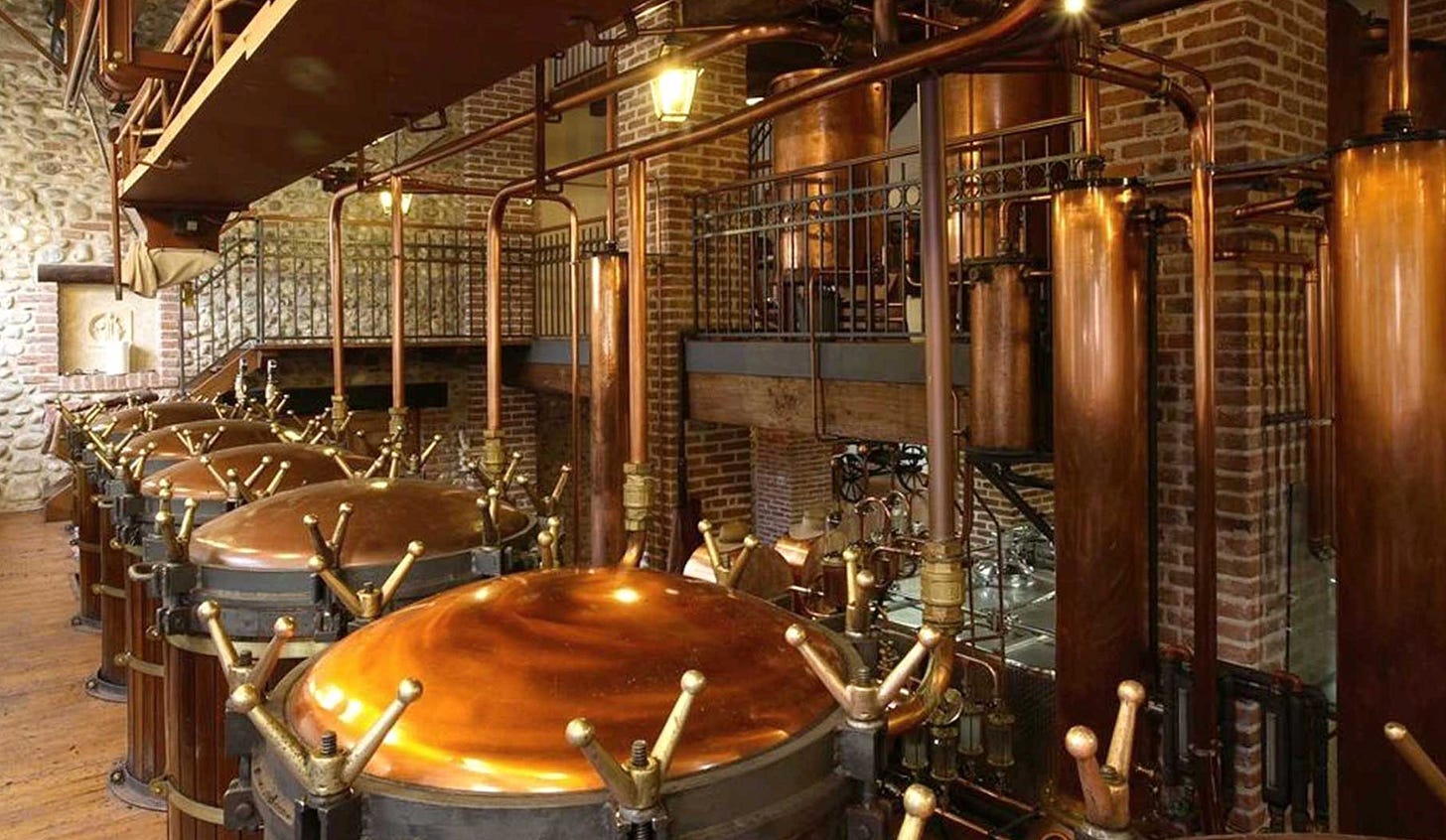

In the 12th and 13th centuries, records show Italian monks were experimenting with grape-based distillates they called aqua vitae, literally “water of life.” Later, in Northern Italy -- Veneto, Friuli, Trentino -- farmers discovered that after making wine they could use the leftover grape pomace (skins, pulp, seeds) to distill a fiery spirit. It was the first grappa, quickly nicknamed the “poor man’s brandy.”

The drink was far from refined. As recently as the 1950s, homemade grappa could be a serious health hazard. Excessive alcohol levels, toxic concentrations of methanol, and the use of lead piping led to consequences ranging from alcohol poisoning and blindness to organ failure and heavy metal contamination.

But that didn’t stop the Italian military from including grappa in soldiers’ rations in both World Wars. For farmers and laborers, it was a low-cost way to relax after a long day’s work. And as Italy became richer in the second half of the century, producers began to modernize: safer equipment, cleaner methods, single-varietal grappas, and experiments with barrel aging. Quality rapidly improved.

Then came the regulations.

In the 1980s, Rome tightened rules on how grappa was made, stored, and sold. But the rules went farther, dictating how vineyard owners could dispose of pomace. They could turn it into fuel, fertilizer, animal feed, or alcohol. The easiest and most profitable option was grappa.

Suddenly, there was more grappa than the Italian market could absorb, most of it a rough, oily, throat-scorching spirit produced to satisfy the legal requirements, not to satisfy drinkers. The low-quality reputation stuck.

Today, more than four-fifths of grappa is still consumed in Italy, where the memories of harsh homemade firewater linger. And when foreign bar owners began stocking grappa in the 1980s and 1990s, they rarely started with the top-shelf options from Berta, Marolo, Nardini, Nonino, or Poli. Instead, they’d opt for the cheap mass-market versions -- often dressed up in designer bottles that looked good on a shelf -- that were little better than what farmers and laborers drank out of their chipped coffee cups after dinner.

A Farewell to Charms

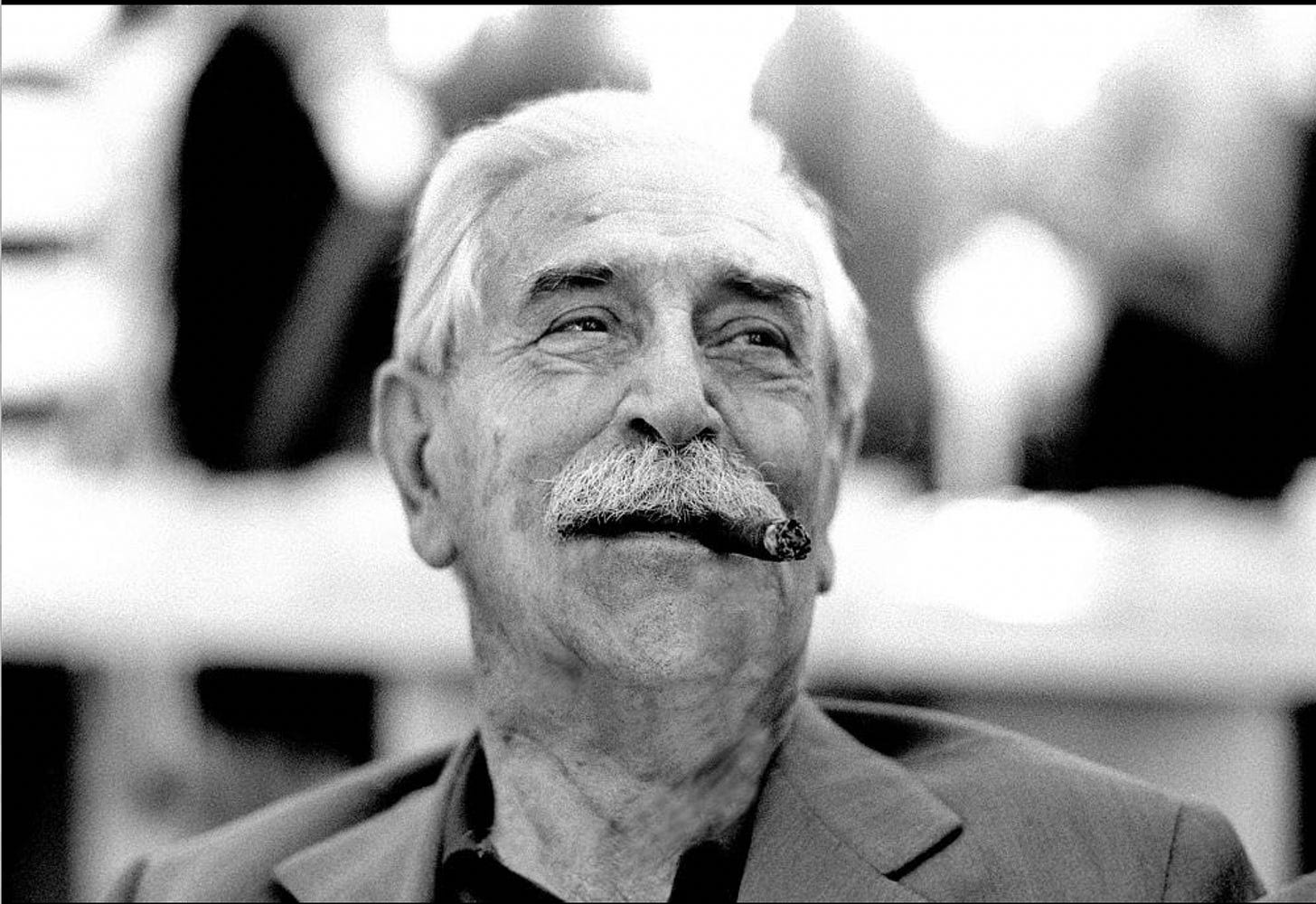

In Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, grappa is a local comfort to protagonist Frederic Henry, who was convalescing from World War I injuries in the Italian Alps.

“I sent for cognac but all they had was grappa,” Henry remembers at one point, calling it a “cloudy, fiery brandy.” But he kept asking for more.

In many ways, Henry’s story reflects Hemingway’s own experience during the war, and by all accounts the author -- who was a Red Cross ambulance driver on the Italian front -- had developed a similar taste for the drink.

There’s a small Hemingway Museum in the heart of grappa country, Bassano del Grappa, between Venice and Trento. And at Finca Vigía, Hemingway’s former home near Havana that is now its own Hemingway Museum, there are bottles of grappa among the personal items left behind when the author fled Cuba in 1960.

The Back of Your Hand

If you’d like to develop your own affinity, there are a few suggestions to keep in mind.

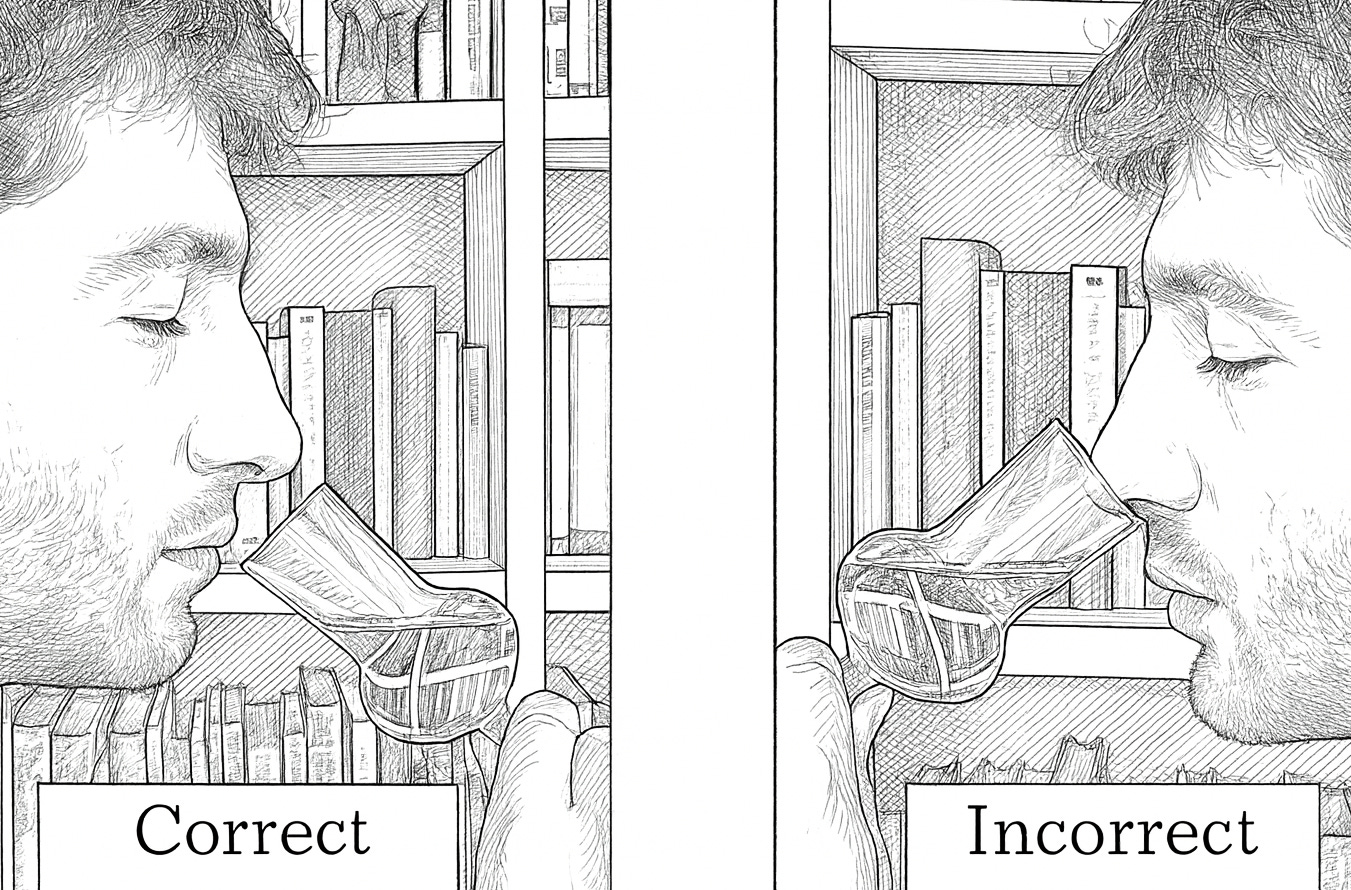

Antonio Nardini, the sixth-generation head of the historic Nardini distillery in Bassano di Grappa, told me once that his favorite way to help new grappa drinkers recognize the subtle aromas of grappa is for them to pour a small amount on the back of their hand and to rub it into the skin. The friction helps some alcohol to evaporate but leaves the fragrant bouquet intact.

I usually suggest a simpler version of the same principle: simply smell from the top of the glass, where the lighter aromas separate from the heavier and stronger alcohol (see the image below).

"There's a connection between the nose and the palate and so taking in the aromas in first can make them more apparent to the taste buds," Nardini said.

The pomace from any grape can be made into grappa, but picking a grappa made from the grapes of light, aromatic wines like Moscato, Glera (the grape used to make Prosecco), or Sauvignon will produce grappa that’s smoother and floral. Pick a grappa made from a muscular and tannic red like Nebbiolo or Sangiovese and it will be more full-bodied and have a stronger bite.

Whichever way you go, a good grappa should taste clean, and it shouldn’t make you wince. Look for fruity or nutty aromas on the nose. If the smell you get is like rubbing alcohol, then … well, let’s say you’ve been warned.

There are only around 125 commercial distilleries in Italy (compared to around 50,000 commercial wineries) and around 30 of them produce three-quarters of the country’s grappa. That means the bottle of grappa for sale in a winery tasting room was probably distilled somewhere else. But it’s still a safe bet that a serious wine producer wouldn’t tarnish the winery’s name by selling a sub-par grappa.

A grappa veteran pro tip: stay away from the elaborate and stylish bottles like the one that contained my first-ever grappa (that one was shaped like the Leaning Tower of Pisa). Those bottles are designed to catch the consumers’ eye, but like a cute design on a wine label it’s probably a way to hide a badly made product.

The glass matters too. The right vessel is a narrow tulip-shaped stem glass, designed to concentrate aromas without burning your nose. Take small enough sips that it warms the throat without scorching it.

Then there’s the question of the grappa’s color.

Traditional grappa is crystal clear, which experts say has been a strength and a weakness. It helps grappa stand out compared to brown, barrel-aged spirits like whiskey or rum, but it probably also reinforces the idea that it’s a harsh, no-frills drink.

It’s increasingly easy to find amber-colored grappa, which sometimes means it’s infused with fruit, herbs, or nuts but usually means it was aged in barrels long enough to extract color from the wood. So, a darker grappa has probably been aged longer. But there are also unscrupulous producers who use artificial coloring to make a lower-end grappa appear to be barrel aged. If a grappa looks too dark for the price, move on.

I drink both. I choose the aged version more often and it’s what I usually suggest for first time drinkers: it’s rounder and easier on the palate, more like a brandy. But when I want to come to a full stop after a big meal, I go for the original clear, potent grappa Hemingway drank.

📌And another thing

When I first read the line from film director and Vino al Vino author Mario Soldati at the top of this post -- “If wine is the poetry of the earth, grappa is its soul” (the original Italian: “Se il vino è la poesia della terra, la grappa ne è l’anima”) -- I couldn’t decide its meaning.

• Did it mean that wine was just easier to appreciate than grappa?

• Was it because wine is more refined and grappa more rustic?

• Or was it because wine is the face Italy shows the world while grappa is more intimate?

• Was grappa the soul because it’s the wine’s “afterlife”?

• Does it mean the wine is cultivated and shaped, while the grappa is simply what’s revealed by distillation.

Of course, there’s no right answer. But over time, I’ve come to believe it means that wine is a collaboration between nature, the winemaker, and the person drinking it. And as a byproduct of the wine, grappa is the concentrated expression of it, a take-it-or-leave-it beverage that’s the wine’s essence.

What do you think he meant?

Yes, OK, there are a few worthwhile things everyone likes (fresh bread, gelato, pizza … The Beatles). But the list is a short one.

What a great post! My first introduction to grappa was in Istria. We stayed at a little guest house in a tiny town called Draguč (Draguccio in Italian, which our host spoke fluently, on account of being old enough to remember when Istria belonged to Italy). Her husband made his own grappa, and when we arrived, they welcomed us with cake and little glasses of grappa. We brought home two bottles of it, and every time I drank it I would remember the beautiful view from the hill town of Draguč.

Grappa… you are not Italian if you never got intoxicated with it at least once. My husband, grown up in the North-East of Italy, got so badly drunk on cheap grappa at 14yo that he only accepted to try it again after 40 years: this time, it was the good stuff, and now he likes it a lot. I like grappa, but not being a big fan of hard liquor I never got sick with it, because my stomach always told me a big NO in front of a first sip of bad grappa. But I must say that offering grappa to the unsuspecting foreigner friend will never stop being the Italian way to challenge and measure their ability to keep their composure, especially when the offer comes from an unassuming elderly lady with a smile on her face.