The Tipping Point

When generosity gets lost in translation

It was one of those nights that makes Italy feel like pure magic. Early May, the final cool stretch before summer. Jasmine in the air. A warm glow from windows. The faint burble from a nearby nasone fountain.

I got together with three friends from my university days who were passing through Rome ahead of a professional conference. We went to my regular osteria on the Via dei Fienili, a short walk from my apartment.

The food was, of course, wonderful, and there was plenty of it: the kitchen kept sending out un-ordered dishes. Mirko, who helped run the place, spoke limited English. So, I helped him explain how his nonna prepared coda alla vaccinara -- oxtail stew -- using dark chocolate to tame the acidity of her rustic tomatoes.

We were drinking one of my favorite wines: Montiano, an elegant Merlot from Falesco, a winery that hugs the border between Lazio and Umbria. We went through three bottles, and, as the meal was winding down, we asked for one more.

“Mi dispiace,” Mirko said -- “Sorry.” We’d drunk all the bottles of Montiano they had.

He suggested a couple of alternatives, but even he didn’t seem convinced. Then his face lit up. “Un momento,” he said, and then trotted off.

A few minutes later he returned, proudly holding another bottle of Montiano, one from an earlier vintage. We were thrilled. He wiped the dust from the bottle with his apron. It was from one of his personal cases of wine in the cellar. He’d forgotten it was there.

When we finished, Mirko placed the bill on the table near me. The dinner had come to 220 euro, but that number was crossed out and 200 was written next to it. But the last bottle of wine wasn’t included. I made eye contact with Mirko and held up the empty bottle with a questioning look. He touched his fingertips together, slowly wagging his hands up and down. “Dai,” he said -- “C’mon, seriously?”

One of the dinner guests slid the bill to his side of the table and said he’d take care of it. He walked up to the counter and started counting out 50-euro banknotes. “One, two, three, four,” he said. Then he added another and said, “And this one’s for you.”

“No, no,” Mirko said. “Is much. One, two, three, four, OK, OK. Five, no. Dai.”

I stood in the doorway and the other two were already outside. The friend who paid the bill walked past me as Mirko protested. It felt awkward. “What’s going on?” I asked.

“I just left him a little something,” the friend said. I told Mirko he should keep the change.

“Is very much, very much,” he said. He followed us out into the parking lot pinching the banknote between his thumb and index finger like an old sock.

The cab pulled up with perfect timing. My friends drove off, Mirko started closing the osteria for the night, and I walked home. I didn’t know yet that what happened would teach me an essential lesson in Italian culture.

Non-transactional

Let me get this out in the open: my default position when I eat out in Italy is not to tip. It isn’t because I don’t care, it’s because I do.

This is unrelated to social class or empathy. I worked in restaurants for years, both in the kitchen and waiting tables, and I know the hard work and seriousness involved. When I eat out, I’m polite, I’m respectful, I’m thankful.

And of course, I’m not going wait cross-armed for a busy server to bring me a few coins in change after a nice meal, and I’m not opposed to leaving a folded five- or ten-euro note (occasionally more) tucked under the base of the empty wine bottle -- or better yet, handed to the server with thanks.

What I am opposed to is institutionalizing tipping. Once a tip is expected, it stops being a gesture of appreciation. It’s a service charge.

It’s difficult for me to understand how there can be debate on this topic, but there is.

The most recent of many discussions I’ve seen was in The New Roman Times, in an article called “The Real Deal with Tipping in Italy.” The gist of it: “If you want to be a better traveler in Italy, you should be consistently tipping the waitstaff and other service workers.”

I could hardly disagree more.

The main argument in the post is that wages for restaurant staffers and other service personnel in Italy are lower than they should be. That much is accurate.

But there are two important contextual economic points to be made here.

First, almost everyone in Italy is underpaid: teachers, law enforcement officers, health care workers, bus drivers, technicians, civil servants, salesclerks, interns -- not to mention all the restaurant staff who aren’t waiting on tables. We can’t tip them all.

And second, comparing wages in Italy to those in the U.S or many other parts of the world is a fool’s errand without including universal health care and education, subsidized public transport, job security, paid parental leave, and a month or more of annual paid vacation.

But I think the most important point to be made isn’t economic, it’s cultural.

The morning after the spectacular dinner I described above, I saw Mirko in our neighborhood coffee bar and by our second coffees -- mine macchiato, his corretto, my treat -- I understood he’d been put off by how things ended.

If he’d wanted to end the evening with more money in his pocket, Mirko didn’t have to give us a discount. He could have charged us for the last bottle of wine: we would have hardly noticed. But what he wanted was for us to have an extraordinary experience -- and we did. But by Italy’s standards, that went unacknowledged.

My friends walked out the door, letting a generous 25-percent tip do the talking for them. But an enthusiastic handshake, sincere compliments on the meal, and a heartfelt thanks would have meant much more.

Post-scriptum:

It’s not just tipping. I’ll probably write about this in more depth in the future but the short version is this: over many years, I’ve watched in dismay as the U.S., my country of birth, and Italy, my adopted home, have gradually imported each other’s worst traits.

In the U.S., politics is growing as fractured and dysfunctional as Italy’s -- progressively corrupt, polarized, and paralyzed. Increasingly cynical Americans are losing faith in their institutions, and birthrates are falling. Couldn’t Americans have taken a cue from Italians’ sense of style, their reverence for beauty, their deep-rooted family bonds, their love of good food and shared meals, their zest for life and culture?

Meanwhile, Italy -- rather than drawing on American economic efficiency, dynamism, innovation, civic pride, and the country’s legacy of social mobility -- has leaned into the least virtuous aspects of U.S. culture: consumerism, chronic stress, ultra-processed foods. Obesity is rising. More Italians are working multiple jobs just to stay afloat.

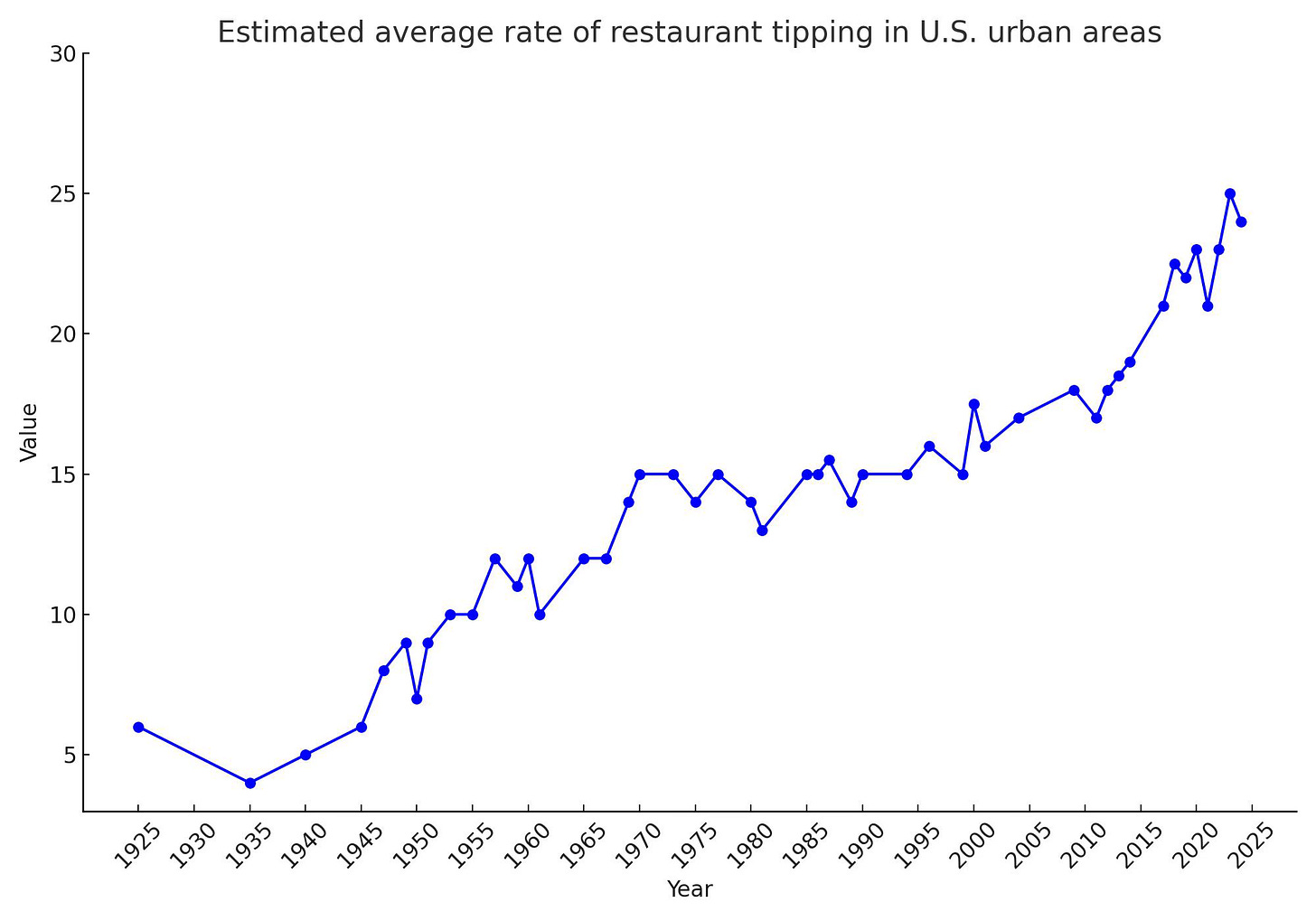

I’m dismayed because -- as a historical look at tipping in the U.S. shows us -- once these trends gain momentum they are nearly impossible to reverse. We’re losing what makes us us and not noticing the cost.

This was both a touchy and touching article to read. Well done!

I should also mention that I could taste that Montiano in your glass. Can't go wrong with Falesco around here... You captured a very real dilemma (for travelers, and for those working in the service industry here). I can't count the number of times I'd seen that total scratched out, or had rounds of wine and after-dinner coffees and amaros "offerti" (offered, as in "complimentary"). As someone with a soul in hospitality, I feel their pleasure deeply in these gestures. All the same, it's painful living here long enough to see things changing culturally-financially and otherwise.

My advice is to follow their lead. A euro or two on the table is a gesture too. It's a drop in the ocean ultimately. It's not going to change the game, but it will buy someone a coffee when they'e digging in their pocket for change. Yes. Some places still only charge a euro! I know a guy who still charges .90. It surprises me every time.

BTW: I've lived in Rome for almost two decades cumulatively. I wonder if we've ever crossed paths!

I appreciated this post, as well as the perspective offered by Laura I. As a frequent Canadian traveler to Italy over the past 20 years, I now find tipping one of the most confusing aspects of my visits. Layer on top of that the post-COVID tipping culture changes, as well as the affordability crisis in most of the Western world, and things get even foggier. While I don't want to be part of the "Americanization" of Italy, I also wonder if I'm already a tourist, and I'm fortunate enough to take a trip half-way around the world, should I not show some appreciation of good service, especially in unaffordable cities? I now sometimes sense that as an "American", I am expected to tip and I usually will oblige, even if Italians around me are not tipping. However, an issue I've run into more than once is with no credit card option, I reach in my purse and find that I have no small bills anyways, or no cash at all, particularly on day 1 or 2 of the trip. Recently, at a fancy but central Florence steakhouse, our young and attentive waiter was crestfallen when we told him we had no cash on us (it was true). My friend and I decided to stop by the next day to give him a tip, but that was only because we were walking by, he was young and genuine and he was working a stone's throw from the Duomo (i.e. no guilt about potentially corrupting the tipping culture of Italy). On the flip side though, is the other side of this conundrum. I had an unfortunate experience on Ischia last summer when a server emphatically told my husband that the tip was not included while also trying excessively overcharge us for a fruit plate that wasn't listed on the menu. All of the Italian tourists around us were having one, presumably not at an insane price. That crossed the line. We argued with him about the price of the fruit, which he sheepishly reduced (supposedly a mistake), and didn't leave a tip.