Wine Land's Redemption

How Italian vino went from plonk to prestige -- and where it goes from here

On my first trip to Bordeaux in the early 1990s, I met an opinionated wine merchant during a tasting at Château Prieuré-Lichine. I was with friends, and we must have been tasting the ’86 or the ’89. One of my friends -- like me, American -- said something innocuous, like “Hey, this is pretty good.”

The wine merchant scoffed. “Mais bien sûr!” he blurted. “Of course, it’s French! The great ones are always French!”

A week or two before, I wouldn’t have questioned the remark. I was a great admirer of French food and wine. I’d been a student of French cuisine. I dreamt about drinking claret with dinner.

But I’d also come to France by way of Milan, where I’d tried my first-ever Barbaresco, from Gaja. Days later, I could still close my eyes and recall the first taste of that wine on my tongue.

When the merchant paused to take a sip from his glass, I meekly offered, “But I’ve had some pretty good wine in Italy --.”

He snapped his head up as if someone had fired a gun.

“Italy! Italy! ITALY!” he bellowed, nostrils flaring. “For Italy, it is easy! A monkey could make good wine in Italy!”

That unlikely exchange helped set in motion a chain of events that eventually led me to live in Italy.

The Chianti fiasco

For most of its history, the peninsula made large quantities of mostly bland, forgettable wine.

Well into the 1980s, most people’s image of Italian wine was formed by the thin, rustic wine that came in a fiasco -- the Italian name for the straw-basket Chianti bottles displayed and served in pizzerias around the world.

“The problem wasn’t the old bottles, the problem was what was in them,” winemaker Riccardo Cotarella told me recently. “The fiaschi were from a time when the wine culture focused only on quantity. Back then, a vineyard could make six or seven times more wine than the same land would produce today.”

That is not to say that Italy did not produce occasional world-class wines over the years. But those wines were the exception to the rule.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, though, a few producers began reducing yields and exerting more control during fermentation and bottling. And by the 1980s, a full-scale Italian wine Renaissance was underway. Winemakers experimented with international grape varieties and rediscovered neglected indigenous ones. They introduced oak barriques, improved vineyard management, and began setting their sights on matching -- or surpassing -- the best wines from France.

Cotarella, who will turn 77 next month, and his younger brother, Renzo, were among a small handful of pivotal figures driving the Italian winemaking Renaissance that gained steam around the time of my Bordeaux visit. Among many other accolades, the Cotarellas co-founded Falesco, acclaimed producers of Montiano, the wine I recalled fondly in an earlier post.

“We’ve learned that every detail counts toward making a top-level wine; nothing can be left to chance,” the elder Cotarella said. “A great deal of what is done must be precise and scientific, but just as much is knowing how to adapt to circumstances. Every wine, every vineyard, every vintage is different. A good winemaker must have a willingness to pay attention and make changes when change is needed.”

The 400 grapes of Oenotria

The ancient Greeks called parts of Italy “Oenotria” -- literally, “Wine Land” -- because the terrain was so naturally well suited to growing wine grapes. That is still true.

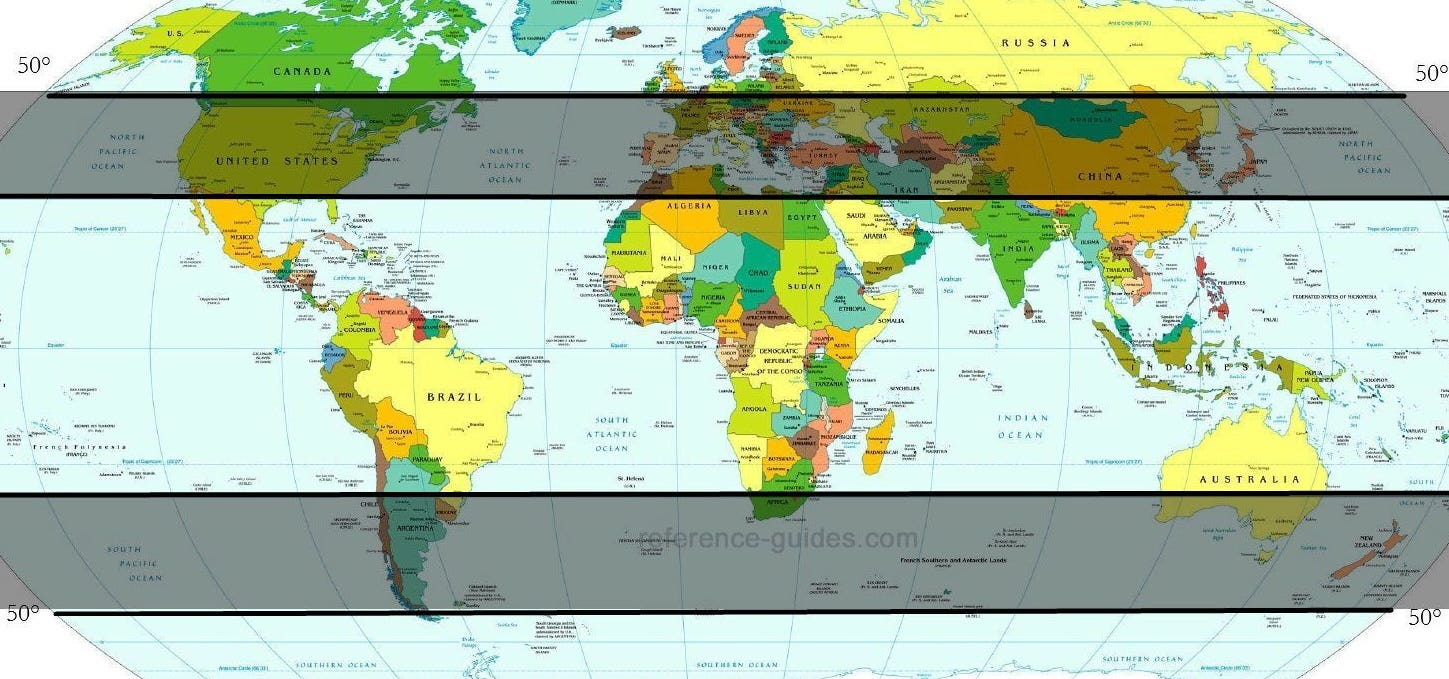

With a few localized exceptions, all the world’s viable wine regions are between 30 degrees and 50 degrees latitude, either north or south of the equator. That is a range Italy nearly completely spans, from Lampedusa in the south (35 degrees) to the Tyrolean Alps in the north (48 degrees).

Italy is smaller than Germany or France, but its length -- note that Turin is closer to Manchester or Copenhagen than it is to Palermo -- means Italian growers can cultivate both cold-weather grapes like Riesling or Pinot Nero and varietals that crave the heat, like Primitivo and Nero d’Avola.

There’s more. Because Italy is a north-south peninsula it is threaded by rivers flowing east or west to the coast, each one of them with south-facing slopes, the ideal orientation for wine grapes in the northern hemisphere. The country’s soils are extremely varied -- volcanic, clay-rich, limestone, alluvial, sandy -- and the country’s long coastline helps moderate temperatures and reduces the impacts of severe heat and cold.

And what about Italian grapes? Around 400 grape varieties are grown commercially in Italy (nearly ten times as many as in France), giving winemakers countless options to express regional identities and complexities, as well as to adapt to both climate change and changing tastes.

The days of high-volume Italian plonk are pretty much gone. But plenty of challenges still remain for Oenotria.

In any given year, for example, Italy produces about the same volume of wine as France. But with nearly 50,000 commercial wine producers -- around the same number as in France, Germany, Portugal, and Spain combined -- the average producer is small. That means many lack the capital needed to invest in the equipment required for the precise, scientific winemaking of the 21st century Cotarella discussed. It also means they lack the volume to build a wide following -- or to scale up if sudden success comes.

“Sometimes there’s a wine I think my customers will like and I put in an order for twelve or eighteen bottles,” said Maurizio Biagiotti, co-owner of Quattro Chiacchiere, my neighborhood wine bar, which specializes in small producers. “But when the order arrives, maybe I’ll only get three bottles. Sometimes only one. So, if a customer likes what they taste and they want another bottle … they’re out of luck.”

The country’s bureaucracy and its bizarre, complicated, and often contradictory wine laws also represent major challenges -- a topic I’ll return to in a future post in The Italian Dispatch. For now I’ll just quote amateur humorist and professional sommelier Anna Luisa Gallucci, who organized a wine tasting I attended a couple of years back.

“To truly understand Italian wine,” Gallucci said, “you need just three things: a highly developed palate, a map, and a lawyer.”

Post-scriptum:

There are circumstances in Italy where it’s an advantage to be neither a tourist nor a native. But in certain tourist-facing restaurants, it is not.

I’ve smiled good-naturedly through memorized spiels that began, “You see, in Italy we have red wine, very good, and white wine, also very good.”

Harder to forgive is when I order a good bottle -- say, a Vino Nobile di Montepulciano -- and the server comes to the table with a modest Montepulciano d’Abruzzo, hoping I won’t notice the switch.

When I do, it rarely produces a mea culpa. “No, no,” an unscrupulous waiter might insist. “This one is better! I thought you would like a better wine!”

For me, that’s the biggest red flag -- far worse than a restaurant implying an obligation to tip big, waiters cajoling passersby off the street, faded stock photos of food on a laminated menu, or even the latest gimmick: someone kneading fresh pasta in a window.

I know my way around a restaurant wine list better than most. I’ve been a sommelier for more than twenty years, and I owned a small vineyard near Rome for nearly fifteen. I’ve taught wine classes and conducted tastings. I’m usually the one who gets handed the wine list when I’m out with friends. In fact, readers who know me well will confirm that I’ve shown remarkable restraint by waiting until the seventh post of The Italian Dispatch to finally write about wine.

But I’m never afraid to ask for help.

Last year I had an unforgettable meal at Glicine, on the Amalfi Coast. Of course, the sommelier, Luca Amato, was knowledgeable. But more importantly, he paid attention. He was curious, not prescriptive. He listened and adjusted. By the end of the meal, he was pouring us small samples of different wines he thought each of us might like and suggesting digestivi I hadn’t considered. More than a year later, my dinner companions and I still talk about it.

But you don’t need someone with a tastevin and a Michelin-caliber cellar to have a top-notch wine experience in Italy. Some of the best recommendations I’ve received have come from countryside agriturismo owners and waiters in humble osterie on the outskirts of the city -- people who take pride in what they serve.

In the right kind of restaurant, the liaison between the customer and the wine cellar -- the waiter, wine steward, sommelier, owner -- is essential. That person knows the wines they serve and how they complement the food. Whether they simply point toward a shelf with a few bottles on display or hand you a thick, leather-bound wine list, assume that they’re not there to run up the bill or unload inventory. They’re there to elevate your experience.

Come back for another dispatch next week.

It turns out I’ve taken the reputation of Italian wine for granted. I grew up in small town South Carolina - my exposure to wine included seeing a “fiasco” in Roman Holiday, my dad ordering a white zin (with his steak!), and eventually drinking (very) questionable vino. By the time I moved to Italy and started developing a palate, the benefits of the Italian wine renaissance were fully in place. And I’ve been enjoying those benefits without ever knowing the difference! Thanks for helping me better understand something I very much enjoy!

I had lunch at a place in Campo dei Fori popular for its carbonara a few weeks ago. The wine list is super interesting with some truly obscure & well priced Lazio wines. I was excited to see one from the cantina Sant’Eufemia (they grow grapes & kiwis!) it’s cheap & light & has an interesting story, all things that were appropriate for the group I was with. The waiter was SO insistent that I order a wine aged in an amphorae (I knew that one too delicious) but not the one I wanted. It was €50. I had to really fight for the wine that I wanted. That had not happened to me in so long.