In Praise of Doing Nothing

Relax: Rome Wasn’t Built to be Seen in a Day

Most of us who have lived in Italy for a while have had this experience:

A friend of a friend is planning a trip and gets in touch to ask if there’s anything they should add to their week-long itinerary that already includes Rome, Florence, and Venice.

“I’ve got three days in Rome,” they might say. “Should I use one of them to make a day trip to Pompeii?”

I’ll sigh and say, “No, don’t go to Pompeii.”

“Really? Then what? Amalfi?”

“No, no, spend the whole time in Rome. Or in Florence or Venice if that sounds better. Or go to Abruzzo instead, or Trieste, or Calabria.”

“But it’s my first trip. I really want the Italy experience.”

I always want to ask, what is the Italy experience?

Sacred and Modern Rome

I’m a collector by nature, ever since I was a kid. There’s a bookcase in my house that holds my favorite novel as a teen, The Catcher in the Rye, in more than 70 different translations. I have more bottles of wine than I’d care to admit. Ancient coins. Art about Rome. Watches. Exotic chess sets. Books and more books.

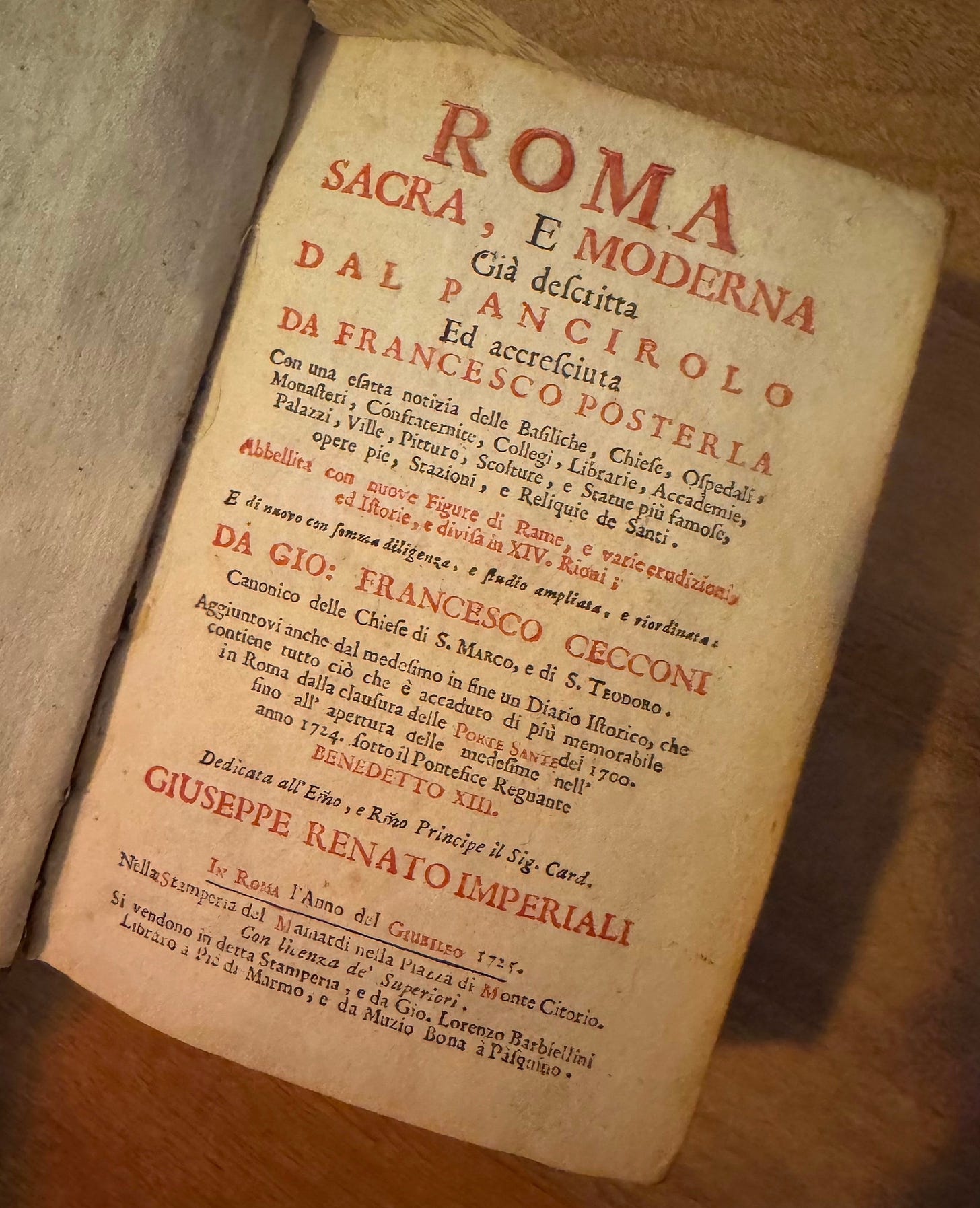

Two shelves are filled with old guidebooks, and one of the oldest of them -- a leather-bound volume called Roma Sacra, e Moderna, from 1725 -- says it takes three days to visit the Colosseum and two more for Piazza Navona or the Spanish Steps. It suggests twenty-eight days to correctly experience the Vatican (to be fair, it also recommends bringing a letter of introduction from a Bishop, in Latin, and arriving with a personal valet -- yes, it was a different time).

Over the three centuries since the publication of Roma Sacra, e Moderna, time frames have obviously contracted. But it now seems to have gone beyond the opposite extreme.

Today, most tourists seem intent on “collecting” sites like they were checking items on a grocery list -- even if that means trading their time for ticket lines, airport controls, or train journeys. It’s enough to make the famous tourism montage in Roman Holiday feel solemn.

But I have yet to hear anyone sum up a trip to Italy by raving about the line for the Uffizi Gallery, the metal detectors at Malpensa, the packed crawl across the Rialto Bridge, or the food cart on Trenitalia.

The experiences that linger are almost always unplanned: a chance encounter with someone from back home, a dinner that stretched past midnight, a stranger’s kindness, a street musician’s cover of a favorite song, or a tucked-away museum or an anonymous church that never makes anyone’s must-see list.

Dolce Far Niente

The phrase dolce far niente can be a little tricky to translate -- I usually interpret is as, “sweet idleness” or “the pleasure of doing nothing.” But as a concept, dolce far niente is a lot more complicated.

I know because I sometimes struggle with it myself. Most people I know do. And when I try to explain the idea, I worry I may sound too “new age” -- something I am decidedly not.

The way I’ve come to understand it is as an unhurried pause that lets your surroundings soak in. Many cultures, mine included, treat leisure as recovery time from everyday life’s demands. But dolce far niente is different; I think it’s meant to be part of everyday life.

The Crush

I don’t know if the idea of “collecting” sites is exacerbated by Italy’s problem with over-tourism, or if it’s the other way around.

Either way, it’s clear that Italy has an abundance of cultural riches, and that most visitors are drawn to the same handful. To borrow some data from an earlier post on tourism in Italy: seven of the country’s 20 regions attracted fewer total visitors than Rome’s Colosseum alone. Five regions had fewer visitors than the Uffizi Museums in Florence or the ruins of Pompeii. Four were outdrawn by the Leaning Tower of Pisa.

Even within popular tourist cities, there’s an enormous discrepancy.

I live in Rome, close enough to hear the bells of one of the four papal basiliche from my living room. There are plenty of shops, fresh food markets, good restaurants, and wonderful coffee bars in the area. It’s just four metro stops from the Colosseum. But I still see so few tourists that I’m caught off guard when I walk through the crush around Piazza Navona, Trastevere, the Trevi Fountain, or the Vatican.

What worries me is that the things visitors say they want most from Italy have been pushed aside in those crowded areas. The parish church with the faded frescoes, the trattoria with the hand-written menu, the piazza where children kick around a soccer ball until dusk … these places are disappearing one at a time.

📌 And another thing

Truth be told, I rarely succeed in convincing determined visitors to downsize their itinerary. But I plan to keep trying.

In fact, I hope this essay might help. At least part of my inspiration for writing this is to have a post I can send to the next friend of a friend who asks whether it’s possible to “do” Cinque Terre in a day or the best way to “get a feel” for Bologna on a two-hour train layover.

I recently spent a few relaxing days with friends near San Clemente, Emilia-Romagna. The town is between two popular tourist destinations -- Rimini on the Adriatic coast and the tiny Republic of San Marino -- but it still doesn’t appear on many tourist itineraries. There was great food and company. The slow pace was an elegant tip of the hat to the virtues of dolce far niente.

While there, something unexpected popped up. It was an afternoon when I’d planned to spend some time by the pool with a book. But someone asked if I wanted to change plans to visit Il Cerro, Italy’s smallest commercial grappa distillery (annual production: 750 bottles). Regular readers know I’m a grappa evangelist. What do you think I said?

Take a look at this misshapen map of Italy. It resizes Italian regions based on the number of foreign tourists compared to the native populations. In summary: Veneto, Tuscany, and Lazio loom large; Abruzzo, Calabria, and Friuli Venezia Giulia are hard to find.

Italy is full of hidden gems like San Clemente -- they’re just too small to find on a map like that.

Would have loved to have read this article before I traveled there. I was blessed with meeting you and having you show me some tucked away places so I got at least part of your experience, which was truly the best part of the visit. I would skip Venice

in a heartbeat to spend another afternoon with you and your friends walking around. Keep up the effort to get people to hear you. You are wise in your words.

Had to laugh. The one time I’ve been to Italy I went to Rome, Venice, and Florence.

We actually stayed the first few days outside of Venice in a tiny town called Vallà, the closest city is Castelfranco. We were there for the babtism of my husband’s nephew.

We stayed with friends of the family. Our hosts supplied us with delicious bread and coffee in the morning and then afterwards we spent time with family at their house or went into town. We were treated to dinner in someone’s home every evening while in Vallà. A couple of nights the grandparents of the baby and one night a great uncle in his huge barn at a long table for about 30 people.

The day of the babtism all of us in the one house left the house together to walk towards the town church. As we walked down the road more and more people from town joined the processional towards the church. It was out of a storybook.

One day we went to meet a close friend of my BIL’s who was a jeweler, and my now husband and I wound up having him make our wedding bands. That is one of the few pieces of memoribilia from the trip.

Rome, Venice, and Florence were a whirlwind. If I go back to Italy I would love to stay a month, mostly living like a local, with a few short excursions.